It’s not so easy to unlearn white sight. It blanks—meaning fails to see what there is to see—for a reason. There are many names for that break in perception—repression, dissociation, block, trauma and all the related apparatus. All are the result of the physical and psychic violences within racial patriarchal capitalism, including but not limited to rape, harassment and abuse.

Here I describe how it took a combination of the pandemic, the police and some photographs to allow me to recover my own experience. It’s a cautionary tale, not a redemptive story of overcoming adversity. Even in a situation where the wrong is self-evident and the perpetrator manifestly vile, the police are the problem not the solution. You’d think I would know that. The power of abuse always comes as a surprise.

The fixed stare of surveillance that sustains this hierarchy is what is called police, the policing of the phantasmic single “self” that is white masculinity. The de-policing of the “self” is the practice of freedom. It begins with the consent not to be such a “self,” or single being, acknowledging the multiple actors in and around a person. Bodies must be autonomous, yet selves are not single.

That contradiction offers a way to “learn how to live, finally,” as philosopher Jacques Derrida had it. For me, it is a late life project, one undertaken in retrospect. People talk about “surviving” abuse. That’s not my experience. It’s a break within, that creates a spectral person from “before” and a dissociative person afterwards.

Dissociation and the “Self”

There’s more than one person involved in the dissociative “self” that is not one. The older ones from before and during are trying to prevent the others from finding certain memories, certain ways of seeing. That’s their job—prevention, censorship. Their tools are dissociation, forgetting, displacement.

What’s it like? A daily example: I have recurrent anxieties about where my keys and wallet are. On the subway recently, I am suddenly concerned about losing my wallet. The next thing “I” know, my hand is on my wallet in my bag. In the brief interim, I had reached down, opened the bag, seen the wallet and reached for it, the work of a few seconds. But the “I” that felt the physical object in its hand did not experience those seconds. The only cue to the missed time was the sensation of the object in my hand. There must be many other times when “I” don’t notice such checking outs. I have no control over them.

The Photograph as Portal

Photographs can be portals to that “dead time,” opening up a way to know those spectral selves, dead but not gone. That connection is not straightforward but works associatively, symptomatically and beyond voluntary control.

In the pandemic, I was dissociative every day. I was marching to defund the police in New York, while helping with the Metropolitan Police with their inquiries in London in order to convict the man who sexually assaulted me back in 1973. Why work with the cops? To try and damage the school where I was abused and to say something back to the abuser. It didn’t work.

The police are central to the apparatus that invisibilizes systemic rape and abuse. They say to us “Move on, there’s nothing to see here.” And in that space of non-appearance, inside the biopolitical and disciplinary institutions from schools to hospitals and prisons, white men find their opportunity to assault and abuse.

In the middle of this time, on March 3, 2021 Sarah Everard was murdered by a London police officer with high security clearance. She had walked from close by where I used to live across Clapham Common on her way home, only to be stopped, using the pretense that she had violated public health laws. Using his warrant card and handcuffs, the police first raped and then killed her.

In January 2023, it was revealed that another a British armed police from the same unit carried out at least 24 rapes that could be prosecuted, with the certainty he had offended many more times. It was further revealed that there are allegations of assault and abuse against over 1,000 Metropolitan Police officers.

It’s not specific to London but to police. The NYPD Special Victims Division is under investigation for “shaming and abusing survivors and re-traumatizing them during investigations.” In short, such violence within the police is the rule not the exception.

Figure 1. Police making an arrest at the Sarah Everard vigil (Chris Bethell, 2021).

When women and their allies called together by the activist group Reclaim These Streets on March 13, 2020 gathered to hold a vigil in Everard’s memory on Clapham Common, British police broke it up with violence, citing virus regulations. Apparently, they felt “distress” at chants like “murderers” or “it should be you.”

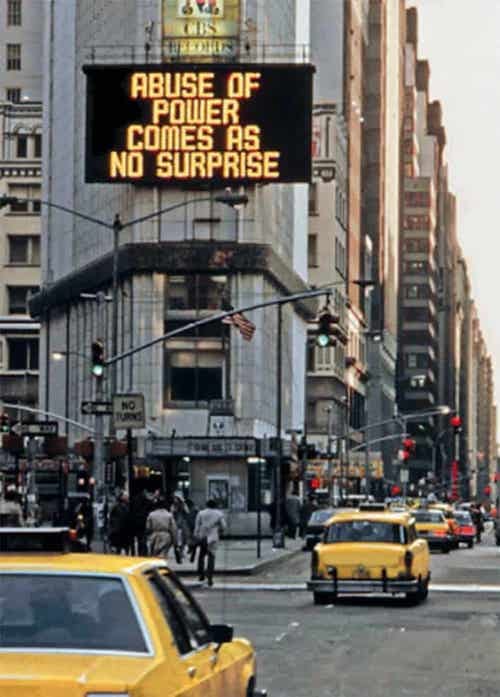

In a widely-circulated photo of the arrests, taken by Chris Bethell (above), a woman can be seen being arrested by three police, while wearing a T-shirt carrying artist Jenny Holzer’s classic “Truism” from 1982: “Abuse of Power Comes As No Surprise.” Her arrest epitomized Holzer’s point—police arresting a woman for protesting police violence against women is both an abuse of power and no surprise. For me, it became a portal to a different set of associations.

Figure 2. Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise (Jenny Holzer, 1982).

Figure 2. Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise (Jenny Holzer, 1982).

As I looked at Bethell’s photo, the reverse of Holzer’s slogan also appeared to be true. While teachers, priests, celebrities, DJs, football coaches, politicians and more have been revealed time and again to be abusers since the uncovering of Jimmy Savile’s lifelong crimes, it always seems to come as a surprise, always the exception not the rule.

Then-Metropolitan police commissioner Cressida Dick called Everard’s murderer a “wrong’un.” In the US, the phrase is always “bad apple,” as in the case of George Floyd’s killer, forgetting that the point of that metaphor is that one bad apple spoils the whole barrel.

There was a further set of unamusing ironies at work. Holzer’s work is one of 22 by the artist in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Most were acquired since then-chair of the Board of Trustees, Leon Black, called for the museum to add more works by women and people of color.

However, Black also paid $158 million to Jeffrey Epstein with which he created legal trusts for Black that allowed him to avoid $790 million in taxes. By the end of March 2021, Black announced that he would not stand for re-election as chair. He’s still on the board. In November 2022, Black was further accused of raping a woman at Epstein’s townhouse, the second rape allegation against him.

Such men abuse and rape in part because there is a vanishingly small chance of being held to account. In the UK, those convicted of rape and other “sexual” offenses serve 4.5 years on average, while the government proposed in 2020 that people should serve 10 years for damaging a statue. While these numbers are always imprecise, there are estimated to be 85,000 rapes of female-identified people and 12,000 of male-identified persons in the UK every year. Offenders are 98% male identified, 78% white. Only 1 in 100 rapes reported to police resulted in a conviction in 2021. It’s less than 1% in the US.

The Swimming Pool Photograph

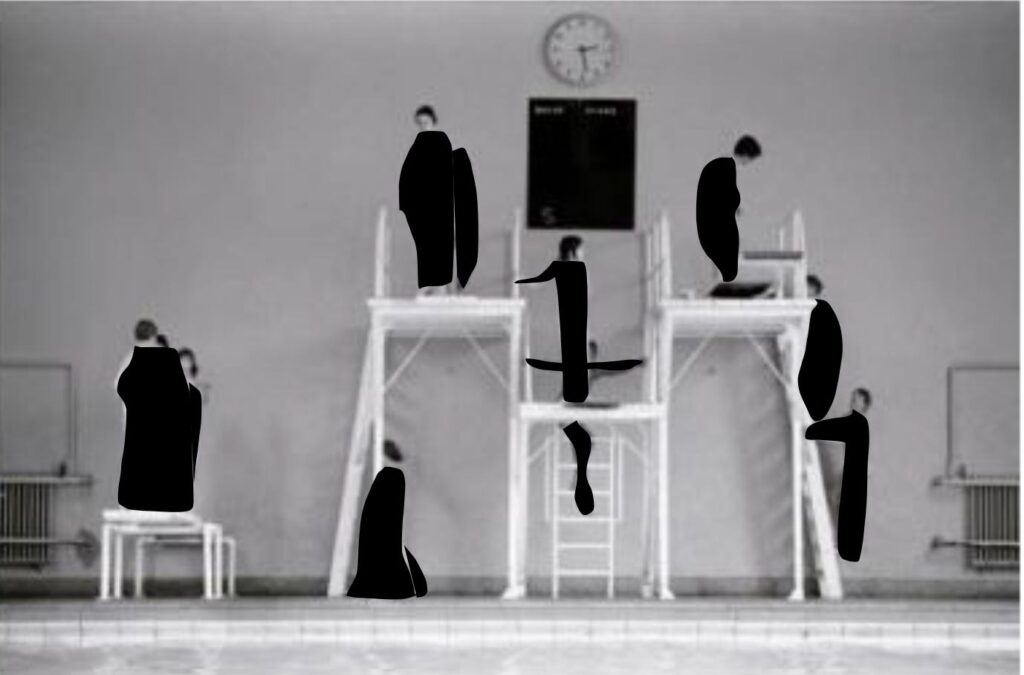

In August 2020, visual activist Benjamin Chesterton was publishing revelations about Magnum Photos and David Alan Harvey’s photographs of rape. He shared with me a photograph taken by Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins in 1974 at City of London school. It showed ten boys aged about eleven clustered on diving boards next to a swimming pool. All were naked.

I’ve redacted the bodies in a deliberately low-res copy of the picture (below). There’s a certain beauty to the figures and the range of grey tones against the bright water and dark blackboard are nicely exposed. But. Why are these children swimming naked and why were they being photographed?

Figure 3. City of London School for Boys, Swimming Pool (Chris Steele-Perkins, 1974; redacted by the author).

Figure 3. City of London School for Boys, Swimming Pool (Chris Steele-Perkins, 1974; redacted by the author).

I had a shock of recognition. The photograph confirmed my own memory of being told to swim naked at St. Paul’s. Later, I found out that this happened at almost all public (which is to say, private fee-paying) schools at the time. Here was a document, taken by chance, that fastened the fragments of memory, that allowed me filled in the blanks.

This grooming accustomed us to apparently bizarre behavior around naked bodies and opened the door to all the rest. A systemic abuser, music teacher Alan Doggett, who created Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat with Andrew Lloyd Webber at St. Paul’s, had even moved from my school to City of London.

Not much remarked on at the time, Magnum had later exhibited and circulated the photograph in a European show called “Players: Magnum Photographers Come Out to Play” in 2016, later shown in Madrid in 2018. Chesterton found the photograph in the published catalog and it had previously been for sale on the Magnum website. Even after Jimmy Savile, no one had seen anything wrong, including the veteran curator Martin Parr and his younger co-curator Christina de Middel.

Perhaps the sheer oddity of the scene caused them to blank on its manifest content. Or perhaps they did a search for “swimming” to go with the facing pages of swimming photographs and, dazzled by their own white sight, didn’t see what there is to see here.

That same August 2020 I was beginning a fellowship at Magnum Foundation (which became remote). The Foundation was loosely connected to Magnum Photos—with no connection whatever to these abusive histories and photographs, I should emphasize. Through them, I was later able to talk with the photographer, Chris Steele-Perkins, after a set of preparatory conversations. I thought it was generous and brave of him to talk to me. While I had imagined all kinds of scenarios, it turned out Steele-Perkins had just walked into the school off the street and a teacher showed him around. Was it the serial abuser Doggett? Or just another white male using the institution as protection?

Steele-Perkins took just this one photo in the swimming pool. Someone from the school later asked him not to use it. They knew what it meant, even then. When asked why he had not been shocked by what he saw, Steele-Perkins paused. He quietly remembered that when he had been a public schoolboy, he was punished by being made to take ice baths naked. So he didn’t see what he photographed as abusive. That’s how the cycle has repeated itself.

Filling in the Blanks

With this reinforcement to hand, I was able to fill in the blanks of my own memory. It became possible not just to file a report but launch a case. I wish I hadn’t. What I wanted was something like emotional justice. Police don’t offer that.

I found the Metropolitan Police to be in turn indolent, ineffective and intrusive. Always eager to discuss the most minor detail of my assault, the simple process of interviewing me, some family members, and the already-convicted offender (on other similar charges) took years. Three different police handled the case.

Everything hinged on the interview with the offender, former teacher at St. Paul’s School David Sansom, who had already been imprisoned in 2014 for similar offenses dating back to the 1970s. While the interviewing police officer came prepared with questions designed to trick him into speaking, she was shocked by his transformative personality. Before and after, he tried to appear sociable, asking standard middle-class questions, like “how did you get here? By train?” In the interview, another personality appeared, sarcastic and insolent, responding “no comment” in ways that felt violent.

No confession, no case. A process that began in 2019 ended in May 2022, as so often, with NFA: No Further Action. The police had lost interest once Sansom had pled guilty in April 2021 to a further set of offenses against boys under 14 in London. The outcome means that the only speech that had consequence in all the years of investigation, whether by police or therapists or myself, was that of the abuser. Because he did not speak, nothing happened.

I was not allowed to follow Sansom’s story in the media as it unfolded, even though it would have helped me understand my own life. Police instructed me that, were there to be a prosecution, all my electronic devices would be seized and searched. Any evidence that I had researched Sansom would be treated as mitigating for the defense. No wonder people don’t go through with these cases.

Police further missed the pattern. Sansom was employed for just a year at St. Paul’s in 1972-1973. During that time he committed offenses for which he was convicted in 2016—and other unrecorded assaults, such as that on myself. But the school, which clearly knew what he had done—because they fired him, despite being stacked with abusers—did not take any other action, allowing the subsequent extended series of assaults to take place.

It’s the same pattern as that in the Catholic church: hush up the offense and move on the offender. In 2020, an independent review found that over 80 offenses were committed by 32 teachers at St. Paul’s School over a period from the 1960s to as recently as 2017. In addition to repeated assault and abuse, one teacher had an extensive collection of child pornography and there was systemic violence against children as young as eight.

The whole damn system is guilty as hell

Has that cycle been broken now? Yes, Epstein, Weinstein, Maxwell and Prince Andrew are gone. It still seems like every TV show I watch has abuse as its “reveal.” Because it’s not (just) about the predatory men (and occasional enabling women) themselves. It’s about the institutions.

People in the US ask me why a school that has enabled violence and abuse for decades is still allowed to function and it’s a good question. Abuse in other public schools has been exposed and sexual abuse is still said to be “rife” across the entire UK school system. It’s going to take systemic change from the school to the hospital, media and perhaps above all the police.

Nicholas Mirzoeff teaches at NYU and his most recent book is White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness (MIT Press, 2023).

Cite as

Nicholas Mirzoeff. “The power of abuse always comes as a surprise,” JVC Magazine, 24 January 2023, https://www.journalofvisualculture.org/the-power-of-abuse-always-comes-as-a-surprise/