Constituting Community out of Water

Eleven rowers perform a circular choreography on a body of water. Behind them, in the distance, we can locate a town on the left, several ships on the water, cranes in shipyards behind them, set to the landscape of the Danube shoreline of Romania. The minute and forty-five second video documents the Romanian national rowing team encircling the location where the island of Adakale used to be– the last bastion of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans in the early 20th century and later “the only settlement that was made up of Turks within the territories of Romania.” The Island was submerged in dam waters in 1970.[1] While the looped video emphasizes the repetitive motion that fails to deliver on the promise of the title of the work, Constituting an Island (2014), it is also suggestive of a performative conjuring: an attempt to remember and revive a community in space and time.

Figure 1. İz Öztat, Constituting an Island, 2014. HD Video 1’46’’, on loop.

This video is part of a multi-piece work titled Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length (2014), a collaboration between the Turkish contemporary artist İz Öztat and her fictional interlocutor Zişan – an Armenian woman who would have lived almost a century before her. Such untimely collaborations with Zişan are gathered under the ongoing Every Name in History is I and I is Other (2012-ongoing) and make up an important chunk of Öztat’s work. In different iterations of this series, Öztat stages encounters with absented histories of modern art, ideas of utopia, migration, and ritual, histories, experiences, and communities of queer and BDSM practices, as well as ethics of community and care, in a confluence of her own timeline and that of Zişan’s fragmented, spectral traces. In this iteration, Öztat pursues Zişan through her escape route out of the Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide of 1915 into the tumult of Eastern Europe in the early years of the 20th century and finds herself in the site of a submerged island on the Danube.

Figure 2. İz Öztat, Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length, Installation view from Heidelberger Kunstverein, 2014.

Born in 1981 in Istanbul, Öztat came of age at the turn of the century, a complex moment defined in Turkey by the escalating civil war the State waged against its Kurdish citizens, the continued and increasingly implausible denial of the Armenian Genocide, and the heightening of a culture war between entrenched Republican secularism and rising political Islam. Around the same time, in the early 2000s, a discourse of multiculturalism took hold in urban centers like Istanbul as the country vied, once more, for European Union membership. Öztat’s work cuts across these various socio-political currents by approaching each moment through a lens that recalls the many violent pasts that undergird and overdetermine them. In doing so, she treats each moment as an aftermath. One of the crucial tenets of this temporal magnification is the relation she creates with geological formations such as watersheds, rivers, and islands and the communities that form around them. By eschewing the violent borders of the nation-state and alliances thereof (such as the EU), Öztat’s work looks beyond the hegemonic epistemes of identity and community.

I investigate the central role of water in a suite of four works that Öztat made between 2014 and 2016: Sculpture for Rainwater Harvest (2014), Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length (2014), Recounting Nightmares to Running Water (2015), and in collaboration with Fatma Belkıs, Who Carries the Water (2015). Though there seems to be an ordering between the realizations of the work, the research for each project and the affects that it engenders seeps into the others. It has therefore been a real challenge to write about these projects in a particular order. This entry holds notes from one of my first attempts to do so in 2021.

Figure 3. İz Öztat, Sculpture for Rainwater Harvest, 2014.

In presenting these works together, I am interested in the bridges that Öztat’s work builds across different histories and their aftermaths. Furthermore, I am interested in the way Öztat locates the Armenian Genocide not in the precise watersheds where it took place, but farther away, in another body of water. Öztat proposes multiple approaches to water: as an exit route, as a source of life, a resource to be protected, as a well of nightmares, as well as the material medium through which to purge those nightmares. Indeed, encounters with and through water (and others have done this with soil and petrol and air) interrupt and complicate our understanding of time by introducing the longer-term geological scale that often exceeds human experience. The currents of water, in particular, complicate what we might understand to be linearity to add perspective, distance, whirls, new springs, undercurrents, countercurrents, evaporation, and precipitation.

Collecting Water

Sculpture for Rainwater Harvest (2014) is an early work that collected water and provided the raw material for the watercolors that have since become an important part of Öztat’s artistic practice. The installation consisted of an apparatus of funnels, pipes, and a large water container placed in Şişhane Park to collect rainwaters. Evocative of cisterns, an architectural and infrastructural technology that collected, stored, and drained rain waters, which can be placed back to the Neolithic Levant, the installation collected 82 kilograms of rainwater over the course of 47 days. Öztat’s initial watercolor series, In the Rivers North of the Future (2014-2017) as well as a video work Recounting Nightmares to Running Water (2015) based on another set of watercolors, were produced with the water Öztat had derived from this installation. The diaristic watercolors using blue, black, and red pigment have become central to Öztat’s practice; introducing a visual language of color, as well as the conceptual metaphor of water to articulate the overlapping, sedimenting, flowing, and staining heterochronicity of time.

Communing and communing around Water

In 2013, Öztat had begun a collaborative research with fellow artist Fatma Belkıs, which took them on a journey to investigate what public space, public resources, and resistance to their extraction, privatization, and securitization meant in the wake of the Gezi Park protests of 2013.[2] Their work led them to grass roots water protection movements in Anatolia, resisting the small hydroelectric power plants that are used by the government as a good excuse to expropriate land, create rent opportunities, package it as service to the people, all while destroying the social, ecological, and heritage worlds of these geographies – not to mention the role these dam projects play, particularly in the more Southern regions, in securitization and militarization.

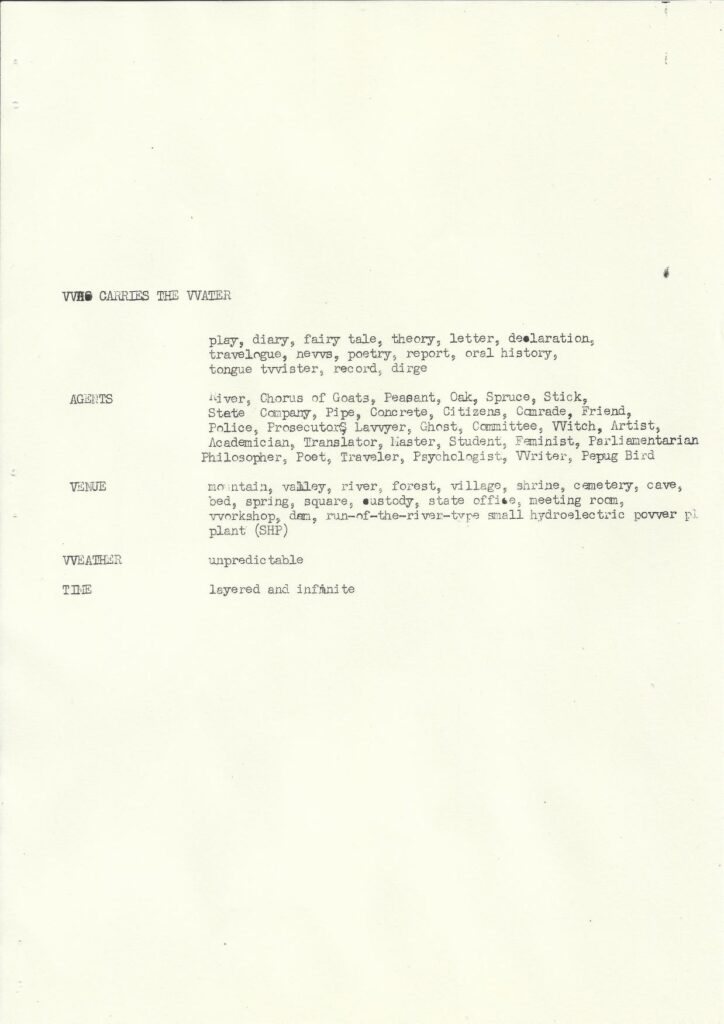

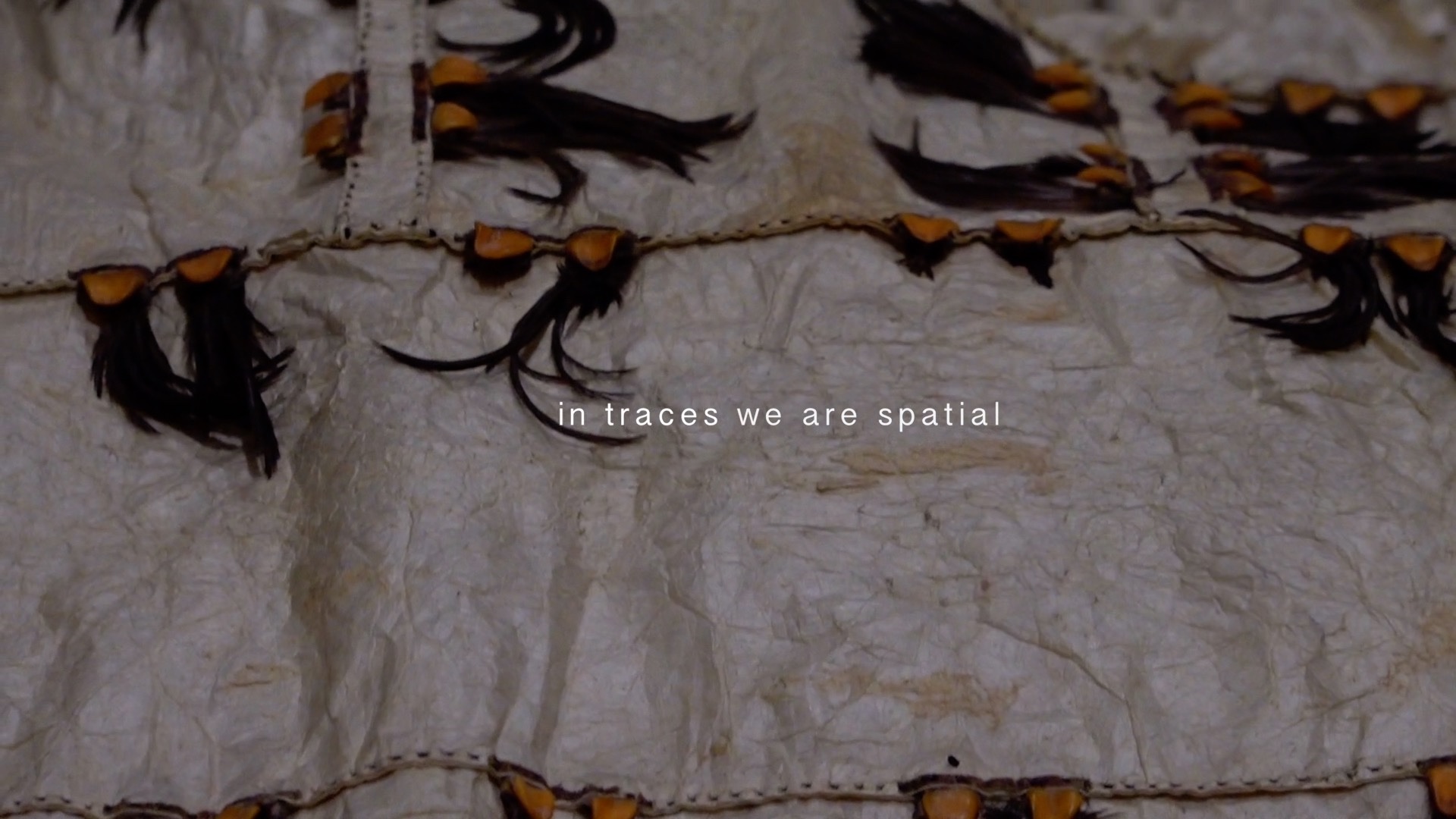

This research seeps into Öztat’s entire oeuvre from the period in question in terms of the affects, fears, and ethics that it engenders. However, the primary output of the collaboration between Öztat and Belkıs take form in Who Carries the Water (2015) shown in the 2015 Istanbul Biennial and the 2017 Sharjah Biennial. The installation consists of traditional kerchiefs, elaborately decorated with woodcut patterns of traditional and novel symbols and a hand-woven basket made from hazelnut sticks and carobs, as well as a typewritten and mimeographed script (the genre of which they define as: “play, diary, fairy tale, theory, letter, declaration, travelogue, news, poetry, report, oral history, tongue twister, record, dirge.” Each part of the installation carries the complexity of time that the communities formed around water resistance movements harnessed. The patterns of the kerchiefs, for example, drew from Hitite reliefs, Armenian tombstone motifs, the local flora, fauna, and symbols of contemporary resistance, to bring them together on the surface of the square kerchief in endless variation. The kerchiefs then, become a canvas for renewing lost relations among human and non-human, as well as the connections between heritages of cultures that have shared geography across time.

Similarly, the script brings together actors human and non-human alike:

River, Chorus of Goats, Peasant, Oak, Spruce, Stick, State Company, Pipe, Concrete, Citizens, Comrade, Friend, Police, Prosecutors, Lawyer, Ghost, Committee, Witch, Artist, Academician, Translator, Master, Student, Feminist, Parliamentarian, Philosopher, Poet, Traveler, Psychologist, Writer, Pepug Bird

The collaboration between Öztat and Belkıs also took the form of an article that they published in the Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies: “Who Carries the Water: Feminist Reflections on Anatolian Hydroelectric Power Plants, Rivers, and Resistance.” It’s form somewhere between field notes and an artistic statement, they write of the script:

We produced a text that put multiple agents into a fictional dialogue with one another, giving voice to human and nonhuman elements. Instead of treating the ecosystem as a background, we treated its elements as actual figures with their own voices and actions to express the agency accorded to them in the stories we heard. In this text the chorus of goats provides contextual narrative information, the trees ally with the local population to resist colonizers, and pipes speak on behalf of state and company interests.

Figure 4. Fatma Belkıs and İz Öztat, Who Carries the Water script, 2015.

Residues of Water

In a works in progress session at SALT Galata, held in early 2015, Öztat presented Recounting Nightmares to Running Water (2015): a nine-minute video work that consist of forty-eight watercolors flowing leftward on the screen with a dream-like voice over narrative. Öztat began her presentation that day by touching upon the history of the phrase, stream of consciousness, tracing its coinage back to the mid-19th century and its use in 1890 by William James’s The Principles of Psychology.[3] The presentation followed a stream of consciousness-style exploration of how multiple languages across different geographies have carried, transformed, and ingrained the conceptual relations between water and consciousness in the 20th century and beyond. The presentation culminated in a screening of Recounting Nightmares. Both Öztat’s research and the resulting artwork thus incorporated the stream in both method and form. The watercolors, composed of different applications of blue, black, and red pigmented watercolors feature blue lines that evoke rivers and blue masses that suggest water bodies. The rightward flow of the paintings in the video collage also recalled a stream, though lacking in the rhythmic complexity of the blue threads in the paintings themselves. The stream would become a linguistic and material trope in Öztat’s research on more than one occasion in this period, appearing not only as a concept but also as a method, a form of expression, and a site.

The voice-over of Recounting gives the impression of knowledge oozing out of one’s unconscious due to its dreamlike narrative laden with a lot of actual information and an almost manic series of interconnections. It moves through references that relate technologies of containment, modernization, and privatization and how these interventions form and transform the relationship between water and consciousness. One of the central strands of this narrative articulates the role of water in the history of electrification in Turkey: the hydro-power system connected to a water mill in Tarsus in the late Ottoman era, the early Republican efforts to domesticate water, and present-day projects that displace and dispossess local populations for hydroelectric dam projects.[4] Encompassing at least a century-long history, the voice-over continues to articulate the weaponization of waterways as natural borders to gain geo-political control in the Southeast regions of Turkey, not only against its designated internal enemy, the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK), seeking cultural and language rights and political autonomy for the long-marginalized Kurdish communities, but also against the country’s neighbors to the south by limiting their access to water. At the center of this geo-political weaponization of water, lies the Southeast Anatolia Project [Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi] (GAP), which consists of multiple dams and small hydroelectric power plants placed across the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.[5] Öztat’s stream-of-consciousness style affords her the agility to relate the more spectacular outbursts of the news cycle to the slow violence that is distributed unequally across the time and space of the nation-state.[6] By collaging fragments from newspapers, articles, graffiti, and conversations with local water protectors and researchers, the stream of consciousness form weaves together events and aftermaths that upend the hierarchical records of historiography. In doing so the form draws out the temporal expanse of the violence and its manifestations through the constraints placed on water and the repression on cultural expression.

The Submerged Perspective

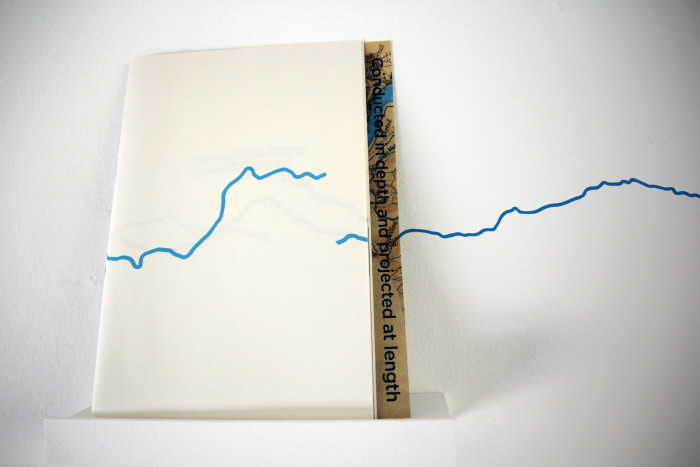

And so, I return to Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length and the submerged island on the Danube. Central to this installation is a delicately bound artist book, which includes an extensive conversation between Zişan and Öztat and reproductions of materials documenting Öztat’s research based on retracing Zişan’s route out of the Ottoman Empire to find the submerged island of Adakale. Inside this book, another smaller insert holds material that is attributed to Zişan, specifically a short story titled The Island of Paradise /Possessed, two sketches of objects that appear in the story, and two maps depicting an island in question.

An abstract blue line cuts through all of these outer pages, the cartographic representation of the Danube is aptly titled; Danube reduced and simplified. A citational practice that brings together an encyclopedia entry, a newspaper article, a dictionary that translates late Ottoman Turkish to contemporary Turkish, runs alongside the fictional/spectral conversation between Öztat and Zişan and the cartographic representation of the river. In the display, the reduced Danube overflows from the confines of the book (and the video installation), onto the table or the wall space –evoking a freeing up of the waters that are constrained by dams as well as maps; in symmetry with the opening up of the imagination this work provokes.

Figure 5. İz Öztat, Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length, artist book, 2014.

This island that was submerged under archival, national, disciplinary, and taxonomic unimagination becomes, for Öztat, a portal into revisiting histories of genocidal violence and forced migrations of the 20th century. In “Submerged perspectives: the arts of land and water defense” Gómez-Barris calls for a “different temporal horizon that reaches beyond the collective narcissism of assumed annihilation” from what she dubs the arts of land and water defense. To this end Gómez-Barris offers the conceptual framework of submerged perspectives, which “attend to those sensibilities, forms of perception, and material practices that are organized below the modern colonial order, and that go undetected by that regime of state power.”[7] In Öztat’s practice from this period, the submerged perspective is but one of the water-related strategies that articulates heterochronic imagination. But perhaps most importantly, Öztat’s work also draws fruitful relations between the capitalist inhibition and appropriation of water with dam technology and that of consciousness.[8] This comes through in both Recounting Nightmares and Conducted in Depth.

The title Recounting Nightmares to Running Water derives from an Anatolian practice of verbal discharge to shed the effects of nightmares, much in the vein of psychoanalytic talk therapy. Similarly, Zişan’s short story entitled Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet [Island of Paradise/Possessed] captures the protagonist [presumably Zişan herself] during a night spent on an island on the Danube while on the run, treading a fine line between autobiographical and ethnographic notes, dreamscapes, and fiction. These practices that develop around the various resonances water holds across media, disciplinary boundaries as well as national borders, I argue, challenge the linearity imposed on time by Anthropocene modernity and resurface the continuities between the exclusionary technologies of empire, colonialism, and the nation-state, chief among them, historiography.

[1] İz Öztat, Conducted in Depth and Projected at Length, 2014.

[2] Fatma Belkis and İz Öztat. “Who Carries the Water: Feminist Reflections on Anatolian Hydroelectric Power Plants, Rivers, and Resistance.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 14, no. 3 (November 30, 2018): 368–73.

[3] In an earlier article, published in 1886, James had used the metaphor of the stream, for the first time, in reference to the passage of time and human perception of it in fragmentary ways. For more, see: William James. “The Perception of Time.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 20, no. 4 (1886): 374–407.

[4] Harun Özturk, Ahmet Yılancı, and Öner Atalay. “Past, Present and Future Status of Electricity in Turkey and the Share of Energy Sources.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 11 (February 1, 2007): 183–209.

[5] For more on the role of waterways in the region’s socio-political landscape, see: Faisal H. Husain. Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire, 2021. Stephen Kinzer. “The World; Where Kurds Seek a Land, Turks Want the Water.” The New York Times, February 28, 1999, Week in Review. Fatma Aslıhan Demirtaş. “Artificial Nature: Water Infrastructure and Its Experience as Natural Space.” PhD Dissertation, MIT, 2000.

[6] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

[7] Macarena Gómez-Barris, (2021) “Submerged Perspectives: The Arts of Land and Water Defense.” Globalizations 18(6): 856

[8] Elsewhere, this has been conceptualized under the rubric of heterochronic imagination, whereby different artistic strategies attend to the persistence of violence through time. Lara Fresko Madra (2022) Historiography and Heterochronic Imagination in Contemporary Art from Turkey (1990-Present). Unpublished dissertation, Cornell University.

Lara Fresko Madra is an art historian, curator, and writer. Her work investigates artistic practices from Turkey and the Middle East, which offer alternative modes of recalling and engaging violent pasts, particularly as a challenge to state sanctioned historiography. She received her PhD from the Department of History of Art and Visual Studies at Cornell University in 2022 and is currently a post-doctoral research and teaching fellow at Bard College’s Center for Human Rights and the Arts.

Cite as

Lara Fresko Madra. “Water-time in İz Öztat’s artistic practice,” JVC Magazine, 17 March 2023, https://www.journalofvisualculture.org/extractivism-5/