On May 29, 2022 a 36-year old man costumed as an elderly woman in a wheelchair threw a piece of cake at the Mona Lisa, shouting at onlookers to, “Think of the Earth! There are people who are destroying the Earth! All artists, think of the Earth!” From behind the bullet-proof glass, Mona Lisa gazed on unperturbed, while the crowd quickly uploaded their videos of the attack to social media. The story went viral, and thus began a flurry of environmental art vandalisms across the world. In the remaining months of 2022, Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (1513–1514), Vermeer’s Girl With the Pearl Earring (1665), Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) and The Sower (1888), Monet’s Les Meules (1890), Klimt’s Life and Death (1908), Emily Carr’s Stumps and Sky (1934), Picasso’s Massacre in Korea (1951), Andy Warhol’s soup cans (1962), and others still, were all subject to splashes of various foodstuffs, superglue and skin. With their hands glued to the walls, the vandals faced cameras, calling for the world to stop its reliance on oil, fracking, and fossil fuels, while onlookers watched a bit bemused, if not annoyed.

Around the world, critics failed to grasp the rationale behind the art actions, asking how attacking “priceless intergenerational [gifts] for the public” was in any way congruous to the environmentalist cause. While these protests have already been critiqued as embarrassing, idealistic, and privileged by mainstream media, this article aims to deconstruct such affective responses, and locate the role of Art[1] in a society increasingly jaded with its social function. That the protestors have risked criminal charges by putting their own bodies, faces, and voices on the line is a testament to Carol Hanisch’s seminal 1970 feminist essay, “The Personal is Political.” Equating “personal problems as political problems,” Hanisch concludes that in lieu of personal solutions, for which there were none at the time, “there is only collective action for a collective solution.” A lesser-known dictum resonates powerfully, complementing Hansich’s proposition; “Art is not a general concern,”[2] Canadian curator Scott Watson uttered, sometime in the early 1980s.

There is a lot to unpack in these two statements on the use-value of Art in society. I read Hanisch’s essay during the formative years of my undergraduate Visual Arts degree, as an introduction to negotiating my own subject position and fledgling politics while making artwork. Years later, it is still a reassuring reminder for any artist in the weeds, but “the personal is political” is only half of the glass—Watson’s statement fills the rest, underpinning the ongoing challenge artists face in a semiocapitalist society of images. Art, with its capital ‘A,’ must be recognized as a unique instance of a commonly understood, already codified set of concerns, channeled into a unique aesthetic experience via the singular ‘genius’ of the artist (or artist collective), presented publicly. Throughout history, particularly in the post-Ford era, artists, curators, and theorists have challenged this status quo in all sorts of ways, but Art has been long defined through the validation of institutions—be it galleries, academia, museums, awards, and so on. This is an ongoing existential challenge for artists, a riddle of how to ‘fail better’ once the process of a project is complete, and in its completion, commodified.

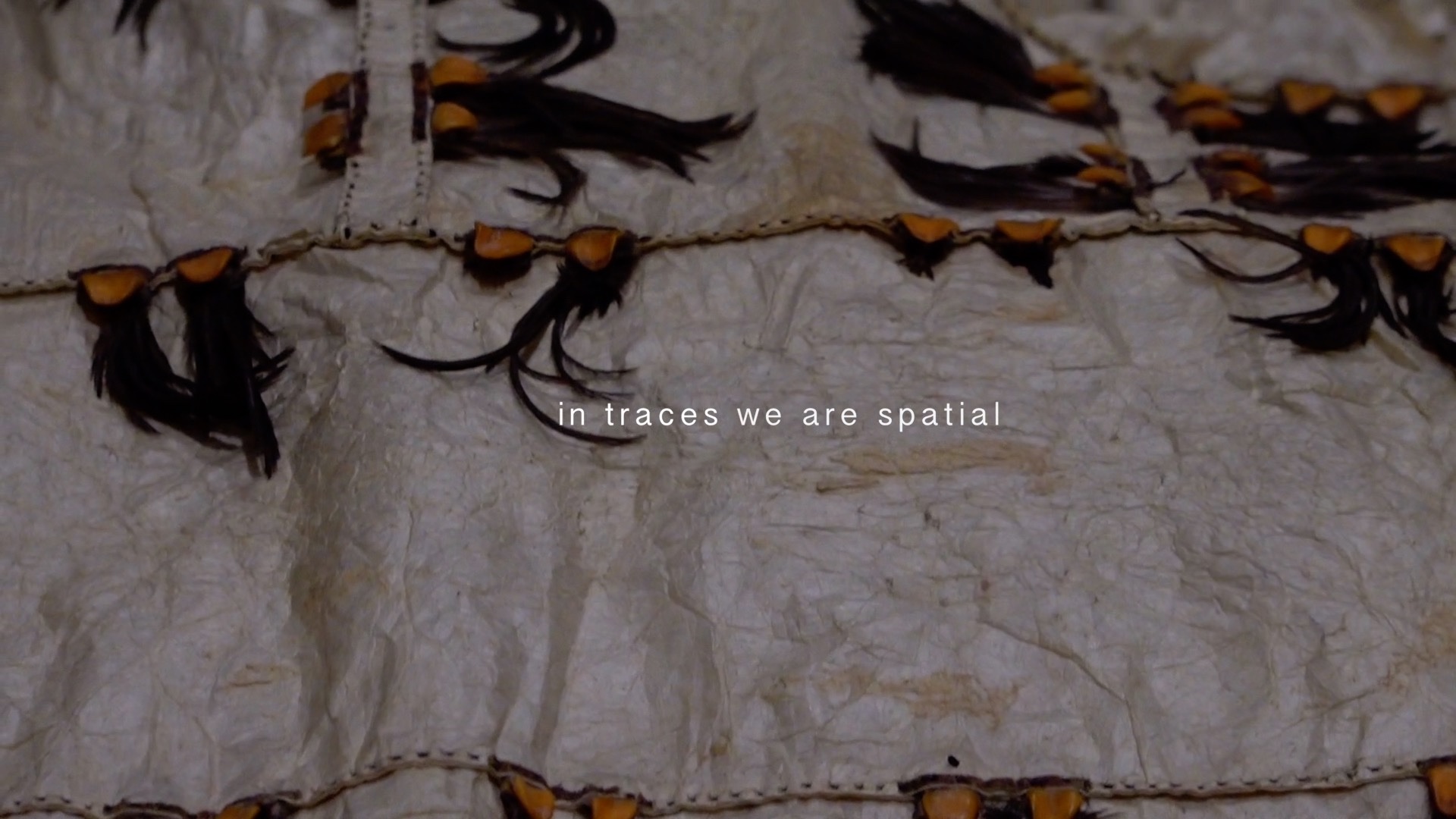

Figure 1. Metro Media office, 198?, Vancouver, BC (image courtesy of Crista Dahl Media Library and Archive).

Figure 1. Metro Media office, 198?, Vancouver, BC (image courtesy of Crista Dahl Media Library and Archive).

Recorded on cassette tape sometime in the early 1980s via the artist-run collective Metro Media with artists Lenore Herb and Angela Kaija, Watson muses that once performance art “gets codified as some sort of art and categorized…then it’s effectively dead,”[3] turning to Artaud’s ‘theater of cruelty’ as a reference point for subversion. Herb responds that true subversion is not possible when the art is state-funded, inviting Watson to run with her logic:

- So, if performance art was really to survive, or flourish, or grow, it would have to find another patron, other than the state.

- In theory, that patron would have to be the people, so that it would have an audience.

- In order to have an audience, it has to become more and more like entertainment to interest the general public.

- Art is not a general concern.[4]

In four moves, Watson neatly checkmates (performance) art’s noble cause. Today, anyone working in the field of art—contemporary, historical, or academic—has had to reconcile the ugly truths of cultural industries with one’s own abstracted, and very personal truths of artistic pursuit. In the same essay-breath, Hito Steyerl writes, “contemporary art feeds on the crumbs of a massive and widespread redistribution of wealth from the poor to the rich, conducted by means of an ongoing class struggle from above”[5] and that Art’s function is “a place for labour, conflict, and …fun—a site of condensation of the contradictions of capital and of extremely entertaining and sometimes devastating misunderstandings between the global and the local.”[6] For Steyerl, contemporary art is an arena in which geopolitics may mix, mingle, collide, and contest, in an aesthetic translation of power into culture. If we take up this perspective, how critics evaluated the art actions make sense: they weren’t very entertaining, they weren’t very fun. While the Hitchcockian strangeness of the Mona Lisa cake incident held our collective attention for a prolonged eyebrow-raising moment, subsequent actions felt increasingly rote, and ever more tiresome. Indeed, climate activists are not performance artists, but by creating a spectacle of their cause in direct relation to the institution of Art, they are effectively activating, and participating in the very subject of their critique.

Instead of targeting red-chip/blue-chip artworks in the highly speculative primary market, activists chose masterpieces housed in national galleries whose symbolic meaning have been successfully reified in mainstream culture, some for hundreds of years. Art historian Lucy Whelan stresses the fact that these works are encased in glass, and after “an astonished intake of breath, [comes] the realization that everything is actually fine.” Her point rests on the protection provided by the glass casing, which renders these acts futile, “proving again and again, that ‘the system’ will save us.” Whelan’s words resonates with curator and art historian Sotirios Bahtsetzis’ thoughts on the function of Art in semiocapitalism, that “various contemporary attempts to restore art’s alleged lost aesthetic autonomy and the non-instrumentalization of artists and artworks…actually prolong the quasi-theological promises of salvation offered by capitalism.” While the activist vandals do not define their actions within the paradigm of Art, the unacknowledged history of art vandalisms which precede their actions are still embedded within our cultural understanding of their acts. It is this history which is omitted and ‘non-visible’—implicated in what anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls “the politics of remembering and forgetting (and thus of history and historiography)”[7]—that has yet to be applied to the actions. While we would like to dismiss these vandalisms as tired tropes the system can save us from, deep down we all know that when the time comes, the system will not be saving us, but saving itself, and perhaps a tiny percentage of us necessary to maintain it. We know we need to change our extractive systems of production, and we know that Art has always been in service of those in power, controlling such systems. This is why we must also interrogate our own affective responses. By critically examining our understanding of how art vandalism has functioned throughout history, we may perhaps arrive at a different critique of these recent gestures for rupture.

Without attempting to excavate a complete historical inquiry on the topic of art vandalism, I will begin in the 1970s, following a hinge moment of the birth of a postmodern politics in 1968–69, at the dawn of the age of modern computing. I chose the following two examples because the vandalized artworks recur later in this article, demonstrating their ongoing cultural significance. First: in 1974, artist (now art dealer and gallery owner) Tony Shafrazi’s spray painted “KILL ALL LIES” on Picasso’s Guernica (1937). When a guard grabbed him, Shafrazi shouted, “Call the curator! I am an artist!” The heavily varnished painting was unharmed, and Shafrazi was charged with five years probation for criminal mischief without trial. In 1980, Shafrazi was interviewed by Ted Mooney in Art in America, recalling his aim to “radically renew [the painting] that had an extraordinary power in its own time, but has since lived off the myth of that power…as it passed into art history.” His intent was to activate the anti-war sentiment of the original work, encourageing individuals to challenge that “invisible [italics added] barrier that no one is allowed to cross.” Second: in 1991, Piero Cannata hit Michaelangelo’s David’s left foot with a hammer, damaging the second toe. “It was Veronese’s beautiful Nani who asked me to hit the David,” he confessed to reporters. Charged with “damage to the cultural patrimony,” Cannata continued to deface both modern and classical artworks throughout the 1990s, before being sent to a psychiatric hospital after scribbling on a Jackson Pollock’s Watery Path (1947) in the National Museum of Modern Art in Rome. In 2005, he was last reported to have spray-painted a thick black ‘X’ on a plaque in the center of Florence which commemorated “the burning death of the 15th-century preacher and reformer Girolamo Savonarola.”

Shafrazi’s Guernica and Cannata’s Michaelangelo are just two accounts of art vandalism documented in artist Felix Gmelin’s project “Art Vandals” (1996–98). Gmelin recreated twelve vandalized artworks, and documented them on a website. Such was the discourse on art vandalism, rooted not only in activism but punk, dada, and madness, which gave their actions a credibility that the present-day climate activists have not been afforded. Previous gestures challenged binary frameworks of institution and outsider, madness and genius, to destabilize aesthetics—perhaps awakening masterpieces from their historicized slumber with a quick slash or spray—without ruffling the institutions of capital foundational to the production of cultural value. In other words, because Shafrazi, Cannata, and the like, did not challenge fundamental principles of capitalism, the narrativization, dissemination, and reception of their acts could be neatly situated within a lineage of art history. Art, as iconography, has long been a mediator in a “tricky effort to read the invisible out of the visible…but the logic of this mediation is all too easy to misread [italics added] as an erroneous version of one’s own ideology of visibility.”[8] Who is misreading, and what is being misread? By reframing the collective response of the attacks as the subject of critique, we may now examine the itching meta-affect driving the investigation of this article, held in the ambivalent tone of Watson’s statement, now 40-some years since he articulated the thought. An ugly suspicion arises: perhaps what is so damning about the art vandals is that they were performing a new kind of institutional critique, one coming from outside the institution itself.[9]

In Sianne Ngai’s 2005 book Ugly Feelings, she uses amoral and non-cathartic feelings of animatedness, envy, irritation, anxiety, ‘stuplimity,’ paranoia, and disgust to traverse between the aesthetic and the political, interrogating the passivity of the modern Bartlybean subject—what we now have termed ‘quiet-quitters’—those who would “prefer not to” engage in neither climbing the corporate ladder nor dismantling the system. While shame and virtue are but two faces of the coin of morality (explicitly not a focus on Ngai’s book), I detect shame as the meta-affect bracketing the collective embarrassment in reaction to the climate activists’ stunts. Such a cringe affect comes from an irreconcilable gulf between content, form, and reception, similar to what one might feel when witnessing slam poetry, or overly emotive performance art. To tackle the task of re-presenting such delicate feelings of earnesty, empathy, and naivety, there needs some combination of poetic grace, self-reflexivity, and practiced confidence. The art vandals’ bombastic acts of perceived ressentiment,[10] unconcerned with the nuances of representation and resulting in little more than a photo-op, triggers responses of shame, embarrassment, and—the most major of all of Ngai’s ‘minor’ ugly feelings—disgust, representing “an outer limit or threshold of… ugly feelings, preparing us for more instrumental or politically efficacious emotions.”[11]

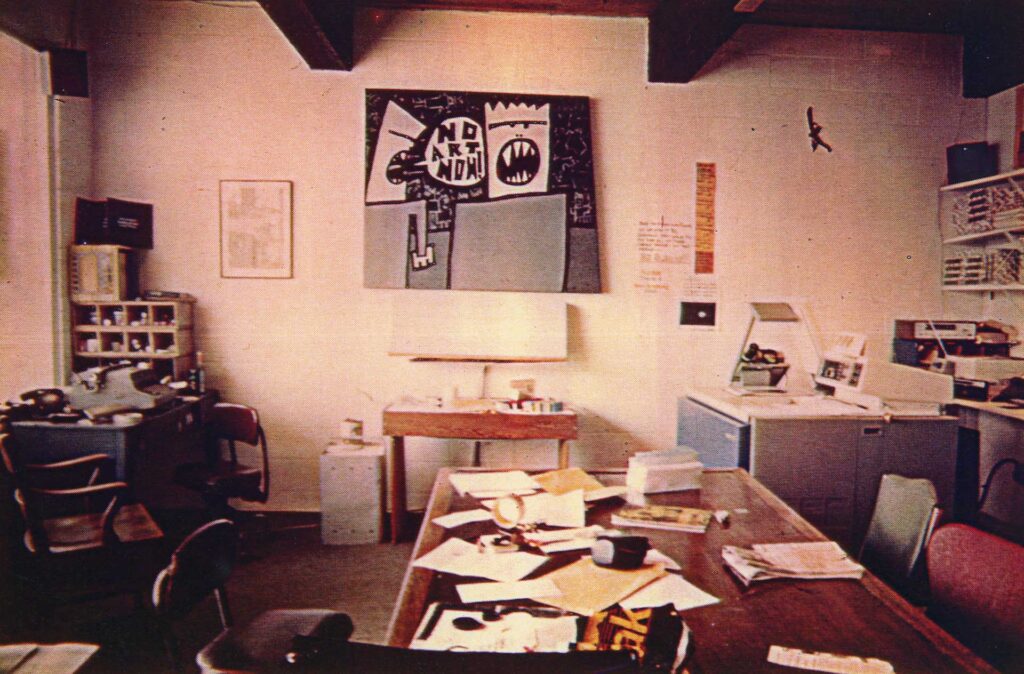

Figure 2. Stop Fracking Around activists threw maple syrup on Emily Carr’s Stumps and Sky (1934) and glued their hands on the wall at the Vancouver Art Gallery on November 11, 2022 (image courtesy of Stop Fracking Around).

Figure 2. Stop Fracking Around activists threw maple syrup on Emily Carr’s Stumps and Sky (1934) and glued their hands on the wall at the Vancouver Art Gallery on November 11, 2022 (image courtesy of Stop Fracking Around).

Now prepared by such a sustained year of collective ugly feeling, how may we move forward in blooming “more instrumental or politically efficacious emotions”? How may we situate the 2022 wave of environmental art actions on a continuum of historical progress, as two elliptical discourses of culture and environment collide? Just Stop Oil, the Extinction Rebellion, Last Generation, Just Stop Fracking, and Stop Fossil Fuel Subsidies have taken responsibility for the stunts, and are just a few of the NGOs in a growing wave of activists lobbying for climate justice. Internationally, these initiatives lead marches, protests, talks, strikes, and sit-ins, as a global social movement in an ongoing effort to pressure governments and corporations to stop feeding and slow down the anthropocene. While the events have been journalistically covered, the acts are not without art historical precedent, as the examples of Shafrazi, Cannata, et al., have shown, and also invite to be analyzed discursively alongside Art’s changing values in society.

Perhaps popular culture is most telling: recent blockbuster films like 2020’s Tenet (dir. Christopher Nolan) and 2022’s Glass Onion (dir. Rian Johnson) provide mass audiences narrative access into fantasy worlds of wealth in which Art plays a central role. In Tenet, the entropy-inversion turnstile pivotal to the plot is located within a freeport in Oslo, where artworks in private collections act as the backdrop for the Protagonist’s quest to save the world from a terminally ill, omnicidal oligarch’s goal to invert the entropy of the world and destroy its past. When touring the freeport security facilities on a reconnaissance mission, Neil, the Protagonist’s ally, asks the freeport salesman what would happen in a fire, as sprinkler systems would no doubt damage the art. The salesman replies, “It will trigger the release of halide gas, displacing all the air within seconds.” “What about the staff?” Neil asks, to which the salesman replies, “Our clients use us because we have no priorities above their property.”

Glass Onion, the second film in the Knives-Out campy whodunnit franchise, sets up a murder mystery on a private island owned by billionaire host Miles Bron. Bron has invited close friends to his mansion, tenderly named ‘The Glass Onion,’ on the eve of launching “Klear,” his company’s hydrogen-based alternative fuel. Inside the Onion, Brons presents to his guests—social climbers of various sorts: a politician, a scientist, a model, social media influencers, etc.—his impressive art collection, which includes the Mona Lisa, on loan from the Louvre. Brons discloses that since the pandemic had greatly put the museum in a deficit, he rented it, and the one currently on display is actually a fake. As the plot turns the planned murder mystery into a real one, Glass Onion culminates with the cathartic destruction of Bron’s art collection by his guests, where no artwork, including the Mona Lisa, is spared.

In both cases, the role of Art is not portrayed as being a general concern at all, but as prizes hidden away only for the world’s 1% to trade, display, counterfeit, and destroy. It is not the first time Art’s value has been used in films to shock audiences with an alternate reality where social order has been disrupted, and our esteemed objet d’Arts rendered so vulnerable. In Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), as Joker’s henchmen deface portraits of American presidents and Degas’ ballerinas in Gotham’s Flugelheim Museum, Joker stops one crony from slicing into Francis Bacon’s Figure with Meat (1954), saying, “I kinda like this one, Bob. Leave it.” In Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006), global human infertility is the cause of war, depression, and religious fanaticism, pushing society to the brink of collapse. The hero of the film, a cynical bureaucrat named Theo visits his cousin Nigel, a government minister who lives in a heavily guarded museum safekeeping masterpieces like Michaelangelo’s David, whose damaged leg is supported by a steel armature. While having dinner beside Picasso’s Guernica, Theo asks his cousin, “A hundred years from now, there won’t be one sad fuck to look at any of this. What keeps you going?” Nigel responds nonchalantly, “I just don’t think about it.”

Whether it is the aforementioned blockbuster films, TV shows such as Netflix’s This is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist (2021) or The Andy Warhol Diaries (2022), or our social media feeds—the consolidation of such variegated content into our streaming devices all but flatten our ability to see the forest for the trees, so the speak. While continued progress in the ongoing consolidation of the modes, methods, and means of communication have provided us, the privileged ‘us,’ with more access to the growingly digitized archive of existence, our critical capacity to hold space for such conflicting and contradicting meaning has some catching up to do. As Art’s social function has all but dissipated into numbers on the blockchain (valuing at upwards of 2 billion USD) and immersive convention center ‘experiences,’ and questions of aura and reproduction come full circle to a new virtuality of authenticity, the pile of historical wreckage keeps growing. The image of climate activists gesturing clumsily towards some kind of rupture—contorting their bodies towards the cameras with hands glued to the walls—recalls that of Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), face turned towards the past, seeing the cumulative catastrophe of progress “which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.”[12] Such a serendipitous resonance shows that history is embedded in our bodies, despite how we might be distracted to forget. The responsibility this article takes is one of memory, to hold up these events in relation to a collective memory that is always in construction, to not disregard these acts solely due to their ineffectiveness at changing the world. To extend Hanisch’s text, there are no individual solutions at this time. What collective solutions that may come from collective actions surely exist on a continuum of the yet unknown, where our goal should be to transform both Art and the Environment into a general concern.

[1] I use a capitalized ‘Art’ to refer to the canon of Art, to which all the vandalized artworks belong.

[2] Elisa Ferrari and KC Wei. eds., Pisces Midheaven: Excerpts from the Lenore Herb Cassette Archive Publication (Vancouver: Vancouver International Archives Week, 2018), 38.

[3] Ferrari and Wei, Pisces Midheaven 36.

[4] Ferrari and Wei, Pisces Midheaven 38.

[5] Hito Steyerl, Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy, in The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 93.

[6] Steyerl, Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy, 99.

[7] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 156.

[8] Arjun Appadurai, “Mediants, Materiality, Normativity,” Public Culture 27, no. 2 (76) (May 2015): 224, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2841832.

[9] Although beyond the scope of this article, there is an expansive field of artists working in social practice that do attempt to reclaim artistic autonomy outside the institution.

[10] Furthering Fredric Jameson’s interpretation of Nietzschian ressentiment as “little more than an expression of annoyance at seemingly gratuitous lower-class agitation, at the apparently quite unnecessary rocking of the social boat,” Ngai concludes that ressentiment is “an antagonistic response to a perceived inequality.” See: Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 34–35.

[11] Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 354.

[12] Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Selected Writings Volume 4: 1938-1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 392.

Casey Wei is an interdisciplinary artist, musician, and writer based in Vancouver, BC, on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. She is a PhD candidate in Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University, where her practice-based research in film-making, writing, and performance are informed by participatory activities such as editing, publishing, and programming. Recent works include the book Tuning to Oblivion: an artist residency (M:ST Performative Art, 2023), and the album Stimuloso (Mint Records, 2022) with her band, Kamikaze Nurse.

Cite as

Casey Wei. “One day a general concern: All artists, think of the Earth,” JVC Magazine, 17 February 2023, https://www.journalofvisualculture.org/one-day-a-general-concern-all-artists-think-of-the-earth/