Lenka: In the latest edition of Venice Biennale (2024), with the title Foreigners Everywhere, the Czech Republic was represented by your project The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter (figure 1). The work deals with colonialism, its legacy, and the ways in which colonialism has shaped human relations with animals. You draw from your long-term research to tell a story of the life and death of a giraffe named Lenka. In 1954, Lenka was captured in Kenya and transported to Prague Zoo. Following her death two years later, her body underwent taxidermy and became an exhibit at the National Museum in Prague.[1] Critical reflections on colonialism and its impact on our present have only recently begun to gain more attention in Czech art and culture more broadly. When did you, in your work, begin to examine colonialism?

Figure 1. Eva Kotatkova (right) and Hana Janeckova (left) with installation of Lenka the giraffe in the preparatory stages of The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter (photo: Aleksandra Vajd, 2024, courtesy of the National Gallery in Prague).

Hana: As you say, in the Czech Republic, critical reflections on colonialism came to the attention of the wider public only quite recently. To me, it has been of interest since I read British imperial history at King’s College London. I have been especially interested in postcolonial Africa. Czechoslovakia’s standing in postcolonial Africa is fascinating and under-researched. In the Czech Republic, colonialism is generally understood as the stuff of the French and British empires. Also, due to Czech history, Czechs tend to think of the Czech Republic as historically occupied instead of an occupying force. Colonisation’s impact on how we understand nature and education, and generally the way European culture has related to its “others” have yet to be adequately discussed.

I curated and co-curated several projects at Display Association for Research and Collective Practice, which explored aspects of contemporary decolonial efforts as an institutional practice. In the pilot project Towards A Black Testimony by the UK-based artist duo Languid Hands, the curator Zuzana Jakalová and I worked together to create a support network for people with diasporic experience who are underrepresented in the Czech art scene. In the three years that the program ran—unfortunately during Covid—in addition to a four-part exhibition programme, we provided a mentoring program, studio space, financial support, and curatorial support for artists from the Afro-Czech community. This is a community formed by relationships of socialist Czechoslovakia with countries in the Global South such as Uganda and left-leaning African countries. The project sought to create support networks within a mid-sized institution in partnership with the Meet Factory residency program.

Eva: I will follow up on this with my activity in the platform Institute of Anxiety. Here I have long been involved, among other things, with the question of animal rights and plant rights in direct relation to decolonial perspectives that question unequal extractivist relations and the search for other models of being together and learning from and with the natural world. For example, the series Factory Farming explored the mechanisms of violence perpetrated on a mass scale against animals and how such treatment of other species is normalized in society. It is part of our cultural imagination, which we have learnt systematically in schools and other institutions.

Hana and I picked up on this point in our 2021 book Animal Touch, which among other things looked at the possibility of disrupting boundaries between humans and more-than-human species through a posthuman sensibility. At the same time, this question is related to the field of education, where I have long been intensively involved—through work with children’s groups, intergenerational projects, and primary school teachers. How we learn and the stories we hear in the context of education strongly influence the image we form of ourselves and the world we live in, the patterns we normalise and internalise and then pass on. At the beginning of the project about Lenka the giraffe, I was trying to make sense of the type of education and narratives which I encountered as a child and which influenced my imagination. I was taught that a cow was good for meat and milk. We were told romanticized versions of the conquest of America. We were taught about the Czech Republic—and its geography—mainly in terms of what kind of natural resources can be extracted from each of its regions. Our project (figure 2) wants to offer a different way of relating to the natural world by working with the body, senses, stories, and polyphony.

Figure 2. Eva Koťátková, The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter, Venice Biennale 2024, Installation view, Courtesy of the National Gallery in Prague, Prague (photo: Aleksandra Vajd).

Lenka: The heart of a giraffe… was positively received both within the context of the Venice Biennale and beyond. However, “at home” – in the Czech Republic – it was attacked by Czech mainstream media as well as some sections of the art scene. What happened and how do you understand these reactionary responses?

Hana: The backlash was, by and large, due to the established understanding of colonialism that I mentioned above. It mostly took place on social media and involved unfounded accusations that in some cases escalated into personal and sexist attacks, even from people who are very well known and respected in the Czech and Slovak art scenes. About two months after the opening of the Biennale, a petition came out. Apart from our project at the Venice Biennale, it criticised other initiatives and institutions in the Czech Republic that were, according to the petitioners, “ideological.” In the Czech Republic, this always means ‘leftwing’. The petition was signed by highly recognized and established members of the Czech cultural elite. Its main criticism targeted the management of other institutions such as the National Gallery in Prague, Jindřich Chalupecký Society, and the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. What unites these different institutions is that they are all headed by women. It is curious that these institutions and, alongside them, our project were labelled “ideological,” as if we had for the last thirty years lived in some “objective” political neutrality. To give an example, The heart of the giraffe… goes back to the year 1954 when Lenka the giraffe arrived in Prague. The 1950s was also a period of profound human rights violations in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. We were criticised that given this context we made the death of an animal a subject matter of the project. Attacks were often very personal, especially towards Eva, who is much better known in the Czech Republic than I am. Her name appeared in all kinds of media, with photographs of the project in Venice appearing alongside derogatory texts and comments.

Eva: I think it has a lot to do with the failure to understand how the story of an animal can be important and relevant, what it can show us if we try to connect to it. However, to be able to do that, we would first have to accept the story of the animal as relevant, which is unacceptable to many people because of the way they have been taught. There were voices on social media and in the public media questioning why anyone would even work on a story of a giraffe, a creature of the “second category,” when political trials were taking place in the 1950s in the former Czechoslovakia, when for instance Milada Horáková—women’s rights activist and democratic politician—was murdered, when things of much greater significance were happening. There were even memes that showed the giraffe and Milada Horáková side by side to emphasize the irrelevance of Lenka’s story of suffering, which for me, I must say, was quite painful. It showed how little prepared we are to see the suffering—or any kind of experience and dignity in general—of more-than-human beings as a legitimate and significant issue that needs to be addressed.

I don’t take these reactions lightly. Far from it. We are now facing an important challenge as we are preparing Echoes of the Biennale, an exhibition that is supposed to bring the Venice project into the Czech context. Echoes gives us an opportunity to introduce the theme of decolonisation to a wider Czech audience, to explore and uncover together the many aspects of coloniality that have been present in the Czech (and Czechoslovak) context and that have affected us all. This also brings about the need to find a more accessible language – whether through words or artistic expression.

Lenka: As you already mentioned, Eva, you have long been involved in the critique of educational institutions, developing alternative educational models. How does this aspect of your work inform the Venice Biennale project? How do you understand the relationship between education and contemporary art?

Eva: One of the ways in which the two come together involves the space of the exhibition itself. Exhibitions have long become much more than just spaces where you need to keep a distance, evasively walk around and avoid touching anything. Today many offer various possibilities of interaction and sensory connection. Educational programmes have become an integral part of institutions’ public programmes and are often created in parallel to and in dialogue with the exhibitions, trying to address the various needs of audiences. This is something I am very interested in. In recent years, when preparing exhibitions, I have communicated with education teams as intensively as with curators. Together we look for the layers and possibilities which do not make it into the exhibition—the physical body of the installation— which we could incorporate through the live programme, performativity, stories, and all kinds of creative and critical activity.

Then there is the second level that involves the character of education itself: what are the methods we choose in our learning? What narratives do we pass on and how do we share them? Can we use creative methods that involve art as a tool or a language? In our case, it is about learning with the natural world, not learning passively about it. The preposition is very important. I’ve been trying to educate myself in critical pedagogy and systems thinking, but also to work with imagination and the senses. These approaches that draw from transformative education are imprinted in almost all my projects. I see a huge potential for emancipation and connection in different ways of learning, including those that are accessible to people with special needs and that bring together people from various social or age groups.

Figure 3. The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter (workshop series with children and senior groups led by Eva Koťátková), 2023, Image from children’s workshop at the Community Centre Nesedím, Sousedím, Prague (photo: Sára Märc).

Hana: I believe in the transformative potential of art education and of artistic strategies to influence the school curriculum. What’s been really inspiring for me is the way Eva works—the amount of time and energy she puts into working with schools, children’s collectives, and other marginalised groups (figure 3). I am both a curator and university lecturer; the question of linking theory and teaching in an art school has been as important to me as the educational aspects of experimental exhibition formats. Before Venice, I was very fortunate to implement various educational strategies in long-term institutional exhibition programmes that focused on accessibility, care, and different bodily experiences such as Multilogues on the Now at Display and Towards A Black Testimony where, as already mentioned, the educational aspect had to unfortunately be very limited due to Covid. What was unique about the programming was that it sought to apply educational principles at the core of institutional practice itself not only for purposes of exhibition, representation and display but also for changing and redistributing institutional practice as a whole.

The methodology of transformative education that was used for The heart of a giraffe… was inspired by Eva’s collaboration with Tereza Čajková, a member of the collective Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures. The workshops that took place in preparation were organized in line with their decolonial methodologies. It is also important to add that the installation in Venice never aimed to be an enclosed and completed work, but a framework that is open to collaboration. The installation was designed to be tactile and materially attractive, but we saw it only as one of many parts, including workshops, discussions with collaborators and interactions with different groups (figure 4). We put these activities, in their importance, on the same level as the artwork at the Biennale. The process-based and participatory aspect of the preparations was very important as dialogues with other people and relationships built by the project, which are for us inseparable from the artwork’s physical manifestation at the exhibition.

Figure 4. Performance “Looking for a Second Heart in a Plaster Neck” as part of The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter, Eva Koťátková in collaboration with Himali Singh Soin David Soin Tappesser, Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, and groups of children and older people (photo: Lenka Vráblíková, 2024).

Lenka: I understand The heart of a giraffe… to be a kind of a ‘school of imagination’—to recall another project you have been involved in, Eva. It is a ‘lesson’ in imagination not only in the artistic and pedagogical sense but also with regards to politics. It is a transformative process that seeks to open a space where capabilities to imagine can be collectively cultivated. Within the framework of hegemonic systems of power that define our world—racist anthropocentrism, neocolonialism, ableism and heteropatriarchy—this is a near-impossible task, especially if it is to be achieved on the affective level rather than only on the intellectual and rational level.

Eva: You describe it very accurately. The goal was to reflect—through the remains of the enlarged, fragmented, and wounded body of the giraffe—on what visions of a future we can imagine regarding our relationship with the natural world, but also on what we cannot imagine and why, what can help us expand our imagination and liberate it. My starting point is primarily artistic. It is still my main language. However, at the same time and especially increasingly in recent years, I’ve felt the need to actively involve myself in various transformative pedagogically oriented projects and thus to be on the ground, in the schools, and so on. To be sure, in these hands-on projects, I’m in the role of someone who brings in artivist practices, who works with the body, performativity and sensory experience, and who develops methods of working creatively with stories. Nevertheless, I learn various methods and skills from the process that I then bring into further workshops—for example those that have intergenerational formats. Intergenerational workshops are the most challenging but often also the most generative. They bring out different and unexpected kinds of collaboration or sharing that is usually difficult to foster for various reasons such as the segregated nature of the public space, which segregates us based on our age and our supposed needs that others predetermine on our behalf.

The School of Imagination focuses primarily on working with the senses and imagination. It looks for new models of working together, relating, and experiencing that can help us face the multiple problems of the contemporary world. It doesn’t address them only through rational perception, but takes the whole body into play, activating sensory channels we often don’t even know we have, allowing us to connect in a group based on shared experience rather than through normative individual identities. Bringing the body back into play is not so easy, precisely because we have let it languish for so long due to the setup of the educational system. It can bring with it all kinds of unexpected emotional or physiological reactions, and therefore all sorts of discomfort. The body then requires a lot of care. However, discomfort is to some extent an important part of the process, it helps us learn how to navigate shaky ground and experience uncertainty. Without it we cannot move forward. Similarly, being able to connect to the here and now is very challenging. You feel like you have been trying to work with your senses and strengthen your imagination, but then you find out how little your body is ready for it in the current system, how much it has been neglected and disconnected.

Lenka: Your work with colonialism and its impact on relationships between humans and animals does not end with the Venice Biennale project. What’s next for you?

Hana: There is one project that we would like to fundraise for and that is about reflecting on the at times Kafkaesque process of preparing this project for the Venice Biennale. As a project that reflects on museum and institutional practices by questioning truth and objectivity through oral history and embodied memory, it would show very well where the sensitive but very important leverage points are in Czech society. Such a project would therefore demonstrate how extractivism shapes our relationship to language and discourse through fact-based methods and chronology for example. It would also reconsider our relationship to the archive, which one has to deal with when one works with institutions like the Zoo and the National Museum.

Eva: Since the beginning of the project, I have been trying to archive the process, including some of the quotes, minor or more major events, institutional interventions, and the like etc. I think that the final form of such a project should not be a frontal performance into which the audience cannot enter, but something based on the principle of Theatre of the oppressed for example or other participatory formats, where the spectators can actively enter and shape the story at some point, or become part of it in some way.

The very motif of the air we all collectively breathe is powerful. Indeed, the oral testimony, which we called ‘the legend’ in the project, was at the centre of the discussions and interventions by the National Museum and the Zoo. However, for me personally, it was the main motivation for taking up the topic. This was part of a story that claimed that the remains of Lenka’s body were accidentally dissolved into a public sewer during the taxidermy process. According to witnesses, it caused a strong smell that spread in the upper part of Prague’s Wenceslas Square which, as a result, had to be closed for a few days. This perhaps can function as a powerful image of a context-specific and embodied view of—or rather oversight of—colonialism: it is not visible, but we all, unconsciously, breathe it in. We all have it in our bodies, we all somehow transform it, we breathe it out and pass it on in chains, but it is not actually exposed, it is a hidden part of the everyday. I imagine that if a play were to be created, the actors and protagonists would be connected by just such a kind of a fog. Bodies that are at first solid then become fragmented, fluid and finally invisible, yet also omnipresent.

In addition, we would also like to immerse ourselves into the live programme of the Echoes exhibition I mentioned earlier. This was not quite possible in the format of a Venice Biennale pavilion, which operates on a pass-through model. A lot of people don’t even stop there, so you can’t really count on organizing lectures or educational workshops and so on. Then we are also very much looking forward to artists invited to the Echo project, who will continue to work with the story and develop it further through performative, lecture-based, and video realisations.

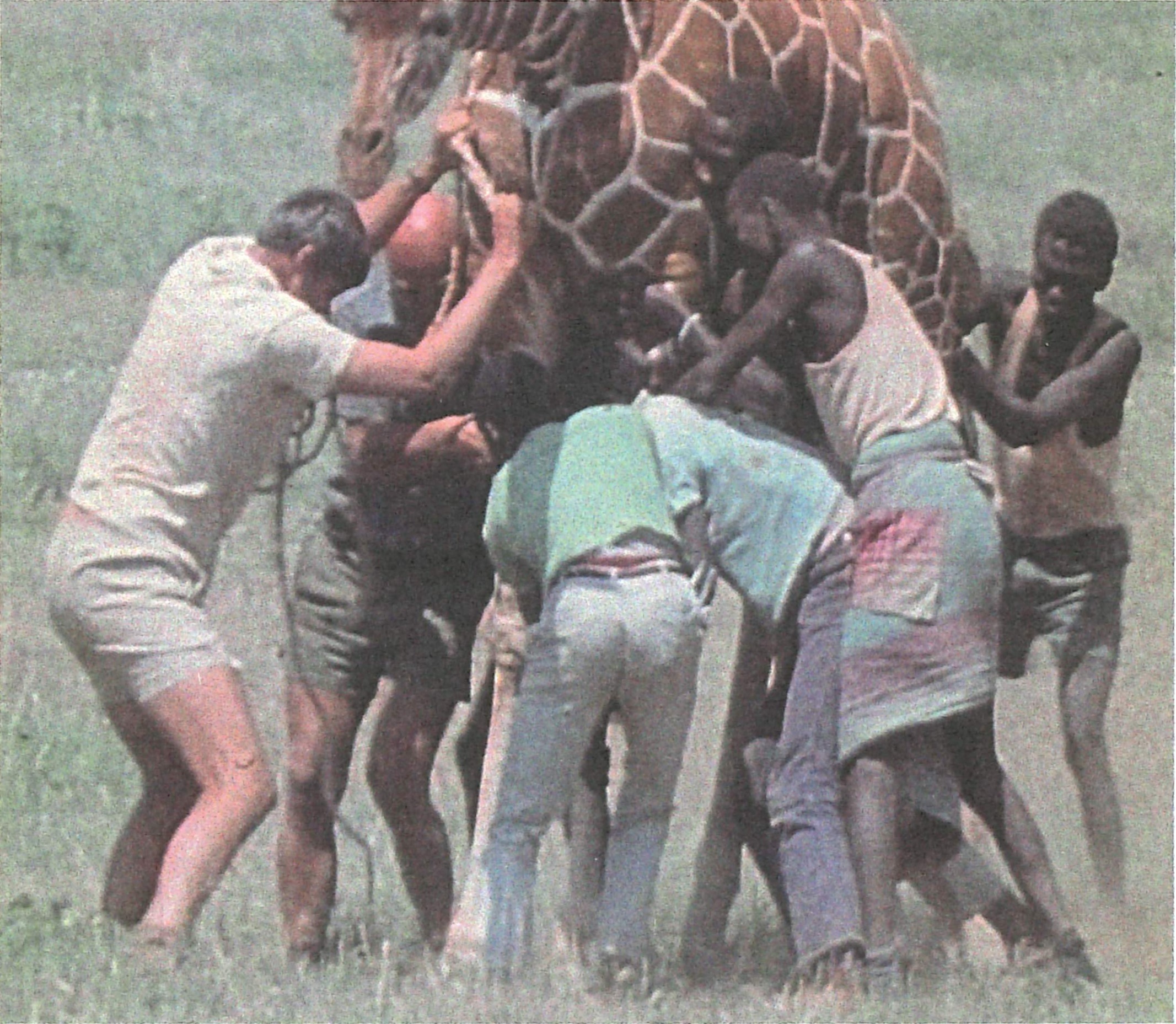

Hana: We are also planning a trip to Safari Park Dvůr Králové. The heart of a giraffe… focused on the fate of Lenka but there is a further history of animal acquisition from the Global South which we deal with in the accompanying publication (figure 5).[2] The story of Czech zoologist Josef Vágner, who was a co-founder and long-time director of the Safari Park in Dvůr Králové is indeed fascinating and not very well known. He imported between two to three thousand animals from the Global South during his lifetime which he often captured by himself. We are very interested in thinking critically about this history and, of course, it might be very problematic as well. Josef Vágner, who wrote numerous books on his trips in Africa and elsewhere in Global South, is considered a very established and respected figure in the Czech Republic associated very positively with conservation efforts—an epitome of the positive relationship with the natural world. Dvůr Králové Safari Park is a respected institution which, at the time of Vágner’s directorship, boasted the largest herd of giraffes in Europe, most of them captured in Uganda. My plan is to direct this research into what Maya and Reuben Fowkes have termed the Socialist Anthropocene, focusing on socialism’s relationship with nature (including animals) and its transformation and exploitation thereof.

Figure 5. Studio Kamarád 522, film still, Czech Television Archive. Image printed in Hana Janečková, 2024, “The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter.’ In Hana Janečková and Michal Novotný (eds.) The Heart of a Giraffe in Captivity is Twelve Kilos Lighter. Prague: National Gallery Prague, p. 35 (photo: Miloš Bobek).

Lenka: To conclude, I would like to ask you about the title. What readings does The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter suggest?

Hana: It is interesting that you’re the first person to ask us this question. I very much like playing with language when working on art projects. In this case, the title is based on misinformation. It is irrationally poetic, bringing poetics to the weight of the situation by mobilizing a poetic imagination that has a certain kind of uncertainty.

Eva: For all we know, a giraffe’s heart can weigh up to 12kg. At the same time, we know that the organs of captive animals shrink. If a captive giraffe had a heart 12 kilos lighter, then she wouldn’t exist. In some metaphorical sense, you could say that she would lose some of her essence, what shapes her in some way. What would be left is a body covered in skin that behaves according to what the confines of the enclosure or the regime of the institution allow her to do. This raises the question of the extent to which animals remain animals when they enter captivity—the zoo enclosure—and when they later turn into stuffed objects. The question relates to the idea children who participated in the preparatory workshops proposed and developed: the idea of returning the stuffed giraffe to the place where she was captured to see whether the herd would take her back, whether the landscape would take her back, whether she would be recognized as an animal there.

Eva Koťátková is an artist, educator and activist engaged with alternative educational models, embodied participation and our relation to the natural world through critical institutional practice, imagination and work with emotions. She co-founded the Institute of Anxiety and the magazine Krunýř [The Shell] and is involved in several educational projects (School of Imagination and Futuropolis: School of emancipation). Recently, her solo exhibitions have taken place at Venice Biennale 2024, Nottingham Contemporary (2023), Arter (Istanbul, 2023) and National Gallery Prague and CAPC Bordeaux (both 2022). Her work has also been, among others, presented at the documenta fifteen (2022) and the 16th Istanbul Biennial (2019).

Hana Janečková is a curator and assistant professor of contemporary and recent art at the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague. Her research focuses on the politics of the body, ecology, critical curating and transnational and decolonial feminism. She is curator of the Czech representation at the Venice Biennale 2024. In 2021-22 she was a Fulbright-Masaryk Scholar at the Institute for Research on Women and CWAH at Rutgers University and the Brooklyn Museum. Her recent publications are The heart of a giraffe is twelve kilos lighter (2024), Animal Touch (2022), Multilogues on the Now (2022) and Nature Red in Tooth and Claw (2023). The first monographic book, Feminist Alliances and Politics of the Body, is forthcoming in 2025.

Lenka Vráblíková is a theorist of contemporary art and visual cultures who specializes in transnational feminisms, political ecology, feminist deconstruction, new materialisms, critical whiteness studies and art education. Her current research focuses on feminist visual ethnomycology (in collaboration with Elspeth Mitchell). Lenka is a lecturer in the Department of Art and Visual Cultures and a member of the Centre for Art and Ecology at Goldsmiths, University of London (United Kingdom). She is also a co-founding member of transnational Feminist Readings Network and a member of the advisory board of the Center for Arts and Ecology Kafkárna (Czech Republic).

Cite as

Eva Koťátková, Hana Janečková and Lenka Vráblíková. “The heart of a giraffe,” JVC Magazine, 10 February 2025, https://journalofvisualculture.org/the-heart-of-a-giraffe/