We are surrounded by advertising that seduces and entertains. Occasionally, it offends. Sometimes it even harms. Media persuasion can cross the line into violence—and often, viewers are compelled, not despite the violence, but precisely because it functions as a form of persuasive intensity. Teleshopping is a case in point. It is a form of television programming dedicated entirely to selling products directly to viewers, often live, with real-time orders and occasional viewer call-ins. Wanna Marchi and Stefania Nobile, known as the queens of Italian teleshopping, are a mother-daughter duo who rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s by selling slimming creams and miracle cosmetics with a style that was anything but soft. They shouted. They emotionally pressured viewers—especially women—into buying. Over 300,000 people became customers of their televised sales. While they were convicted of fraud and extortion in the 2000s, their visual cultural harm has gone unnoticed: images that promised beauty and sold violence as salvation, turning insecurity into spectacle and profit.

In writing about Marchi and Nobile, I have three main motivations. First, although I never watched their live broadcasts, like many Italian women of my generation (born in the early 2000s), I have been affected by their legacy like second-hand smoke—through televised trials, memes, and grainy clips circulating in the media bloodstream. Their cultural impact has always been a strange cocktail of fascination, discomfort, and reluctant amusement. This article, therefore, is shaped not only by academic inquiry but also by personal resonance. Second, their tactics, though extreme, feel eerily familiar. The volume may have dropped, the edges smoothed, but the emotional coercion, gendered pressure, and promise of transformation persist. In other words, this story is a mirror held up to the glitter-dusted violence embedded in advertising itself, in which marketing sells us our own insecurities. Third, despite their notoriety, they remain understudied in visual culture scholarship. They are tabloid fodder, not material for academic studies, and I aim to fill this gap. My contribution is to reframe their fraud as a case of visual and symbolic violence.

In what follows I offer a visual cultural analysis involving image theory, media semiotics, and personal narrative. I conduct close readings of visual and linguistic strategies (body language, camera angles, slogans, exclamations) based on selected teleshopping clips and contemporary interviews. Using Roland Barthes’s concepts of denotation and connotation—literal elements and loaded meanings—I unpack in two sections the layers embedded within Marchi and Nobile’s televised images. First, I situate Marchi and Nobile within the Italian context that enabled their success. Drawing on theories of visual violence, I argue how their shouting images were not anomalies but symptoms of a broader violent culture. Second, I zoom in on their weaponization of emotions, intimacy, and sincerity. Through the lens of theories of offensive imagery, I contend that they crafted offensive televised images while marketing psychological, economic, and interpersonal violence.

Creams and screams as symptoms of a broader culture

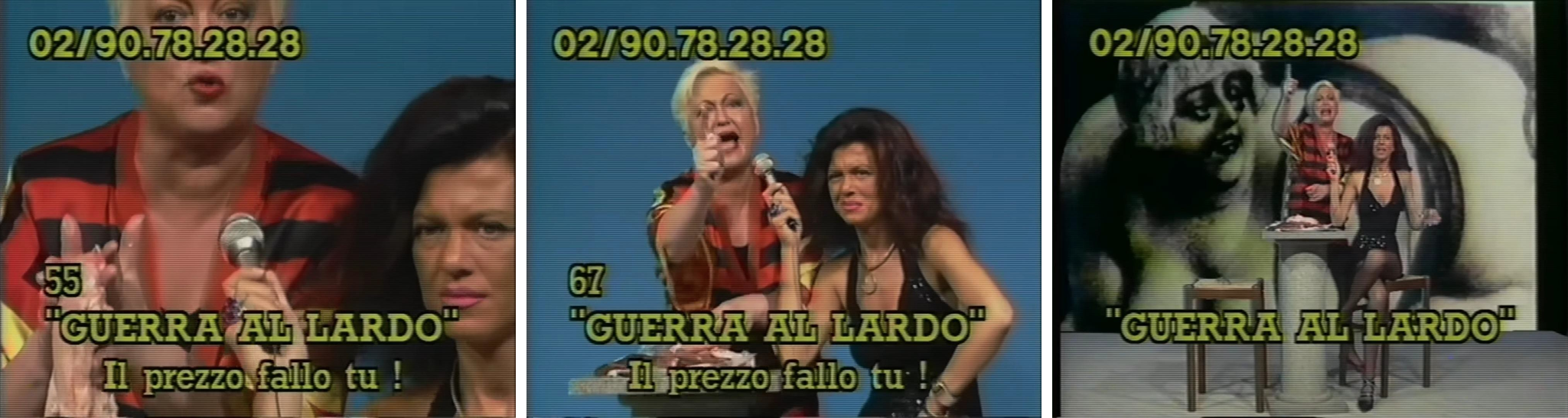

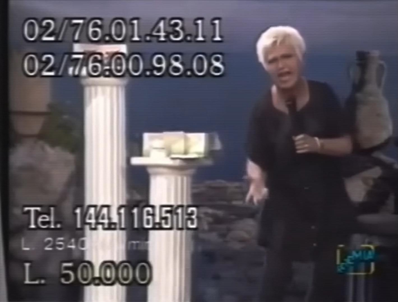

I begin with a frame from one of their broadcasts (figure 1) to help orient unfamiliar readers and highlight advertising’s power to condense emotion, ideology, and desire into a single frame. It features phone numbers in large white digits and a price in yellow—a bargain, Marchi insists, for salvation—dominating the screen and conveying urgency. Behind, Marchi appears mid-scream, gripping a microphone. Bleached pixie cut, black outfit, contorted expression: the connotation is militant intensity, power. Two white neoclassical columns stand tall, product boxes perched like offerings. The columns evoke purity and ancient authority; the creams become sanctified. In the background, we observe a synthetic Mediterranean scene (amphora, stones, seascape) blending neoclassical fantasy with seaside postcard. The effect is theatrical: a Greek tragedy for the living room. But there are no gods, only Marchi. No prophecy, just shame, and her selling the solution to achieve the beauty dream. We see her standing like a high priestess of transformation, dispensing judgment. This image captures the seconds before hawking Sistema Deli, a miracle cure promising five kilos lost in seven days. And she sells the shame, roaring:

You’ve spent your life gorging yourselves! … You’ve looted the supermarkets! You even ate the neighbour! You ate everything you could find! … Shame on you! Shame on you! I said shame on you! Shame! On! You! … Come on, fatty! Oh, you fat one! Oh, you lardy! Are you going to answer me? … So! What do you want to do? You want to slim down? Then you have to go through Wanna Marchi.

Call the number, pay the price, and the excess (the fatness, the shame) will be melted away.

Figure 1. Still from a 1990s televised sales segment aired on the local TV station Telemia. Screenshot from YouTube video wanna marchi gentaglia (@cpennetta, 2021).

I watched and listened attentively to these images when I was nine years old, having an afternoon snack with my grandmother—a slice of cake we had baked together. During her favourite celebrity gossip programme, they aired again. I felt personally addressed and hurt especially because, in the original Italian, Wanna uses feminine grammatical forms, indicating that the invective is directed at women. I swallowed my bite quickly. The hunger was gone.

The words Marchi uttered were the hallmark of 1980s and 1990s Italian teleshopping—a hybrid of commerce, entertainment, and theatre. Teleshopping promised a direct line between problem and solution—no glossy campaigns, just someone in your living room telling you that you could be better and that they had the one thing to make it happen. People listened. As Italy’s post-war economic boom faded and private television networks proliferated, daytime TV audiences—composed largely of women, homemakers, and retirees—emerged as both the core viewership and the ideal commercial target.

Television at this time became a constant background presence, “an important aspect of the day-to-day experience of women, … listened while they were engaged in domestic labour, housework and child care.” I think of my grandmothers alone at home, cooking or folding laundry, with the hum of the television filling the silence, marking the rhythm of the day, and turning advertising into companionship. Television installed a sense of unquestionable truth; it presented the world as if there were no decisions behind the framing, no studio, no unidirectional microphone, no camera operator.

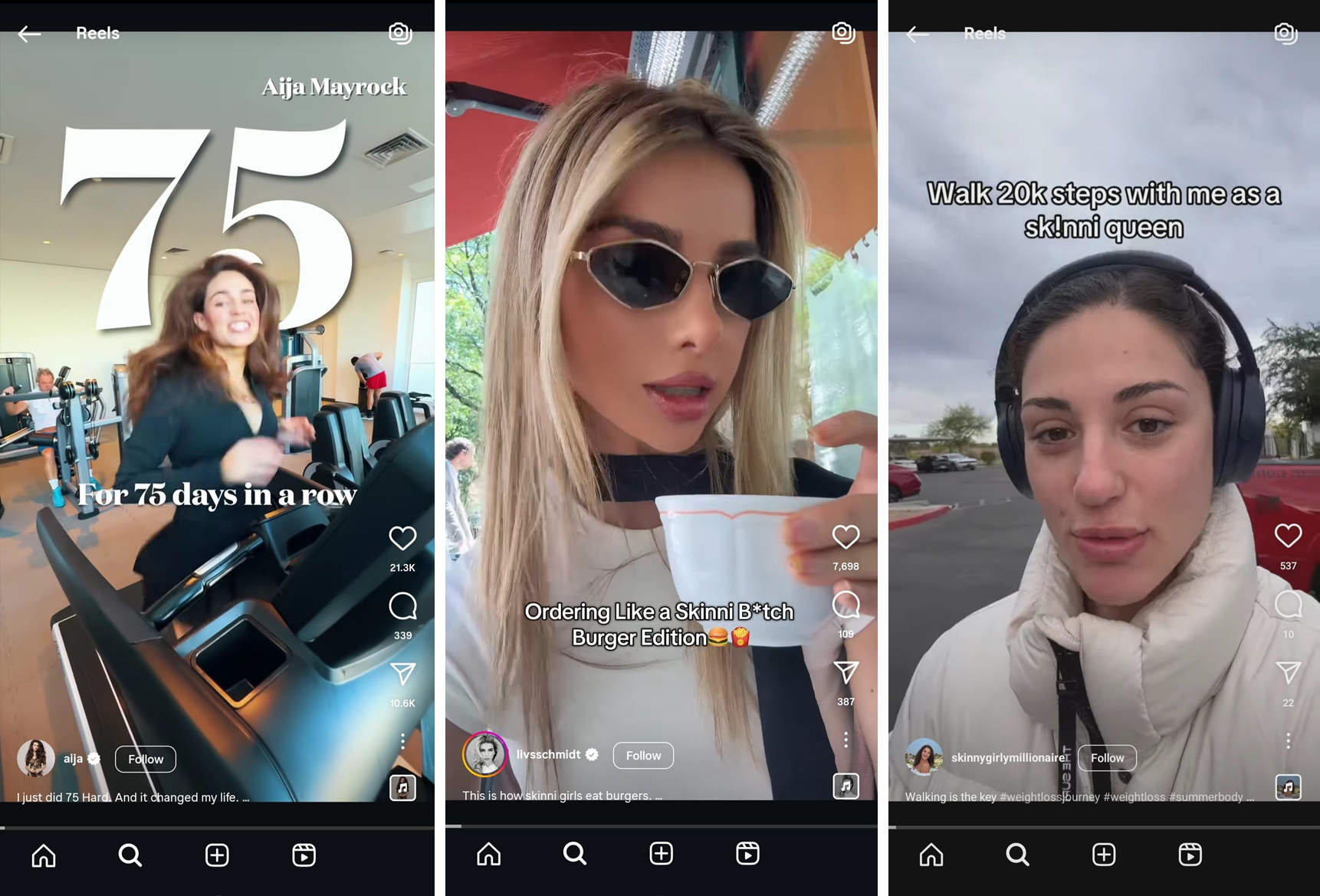

Marchi and Nobile rose to fame in 1986 through the televised sales of Scioglipancia—literally “belly melter”—, a topical cream purported to dissolve fat. Their most loyal viewers and customers were predominantly women striving for control over their bodies and self-worth, often with limited formal education and few critical tools to question the promised transformation. The logic underpinning this promise remains familiar today (figure 2): “fashionable popular” influencers on platforms like Instagram continue to promote flat-stomach empowerment while shaming perceived laziness. What Marchi and Nobile did was to turn up the volume—sharpening the message into a spectacle of bodily anxiety and aspiration.

Figure 2. Screenshots from Instagram Reels (from left to right): I just did 75 Hard. And it changed my life(@aija, 2025), This is how skinni girls eat burgers. Stay skinny. Stay spoiled. Pick your spot and make it worth it (@livsschmidt, 2025), and Walking is the key #weightlossjourney #weightloss #summerbody #walk (@skinnygirlymillionaire, 2025).

Otto Von Busch approaches fashion as a mimetic social game, propelled by the fear of falling behind and becoming a “loser,” a process amplified by cultural narratives and emotional manipulation. Anthropologist René Girard suggests that we are all, to some extent, “mild bulimics,” compulsively regulating our bodies, metabolism, and weight in response to social pressures. The teleshopping set, I argue, was a stage of status anxiety that repackaged domination as entertainment. It was Marchi and Nobile who shouted who the “losers” were, weaponizing the desires for imitation, control, and transformation. Given that they also used feminine grammatical forms in their outbursts, they enacted a form of gendered violence that targeted women while also posing as female empowerment.

The pleasure of imitation comes at a social cost: distinction and exclusion. Otto von Busch and Ylva Bjereld argue that fashion operates as an everyday site of violence, where microaggressions and bullying emerge from the need to preserve exclusivity. Imitation elevates the admired, but to remain on top, they must exclude through microaggression. Fashion thus becomes a legitimized form of violence, reinforcing hierarchies of superiority and desirability. Marchi, as high priestess and judge, publicly shames the “losers” (figure 1). The stage becomes a space of power, where social distinctions are not only visible, but weaponized through bullying: repeated attempts to cause discomfort through an imbalanced power relation.

To fully grasp how this weaponization reflects a broader cultural condition, I turn to Johan Galtung’s theory of violence. He distinguishes between three forms of violence: direct (as an event), structural (as embedded in systems), and cultural (as enduring norms). Marchi and Nobile’s shouting might appear as direct aggression: verbal abuse hurled through the screen, that explodes into excess to make its presence felt. But when situated within Galtung’s framework, these screams and creams also become categorizable as structural violence: the gendered panic around beauty, poor education, and exploitative media practices. They also enact cultural violence, where humiliation is reframed as entertainment and beauty ideals are positioned as moral imperatives. These voices reflected a society that taught women they were failures if they did not conform to aesthetic norms. Fashion and advertising operated here as a mechanism of exclusion, normalizing idealized bodies and transformation narratives, and legitimizing disdain towards those who fail to improve.

What Marchi and Nobile did was name the ambient insecurity and sell its solution. Have a belly? Buy the Scioglipancia cream. The harm resided in the script itself: dissatisfaction was transformed into revenue, desperation into capital. The logic they embodied—the “collective trauma” of “ugliness” and “fatness”—has not disappeared. Today, glow-up tutorials and soft-spoken shame on new platforms (figure 2) echo the same dynamics, proving that the structural and cultural violence Galtung theorizes continues to be broadcast.

Emotional manipulation, theatrical intimacy, and televised sincerity

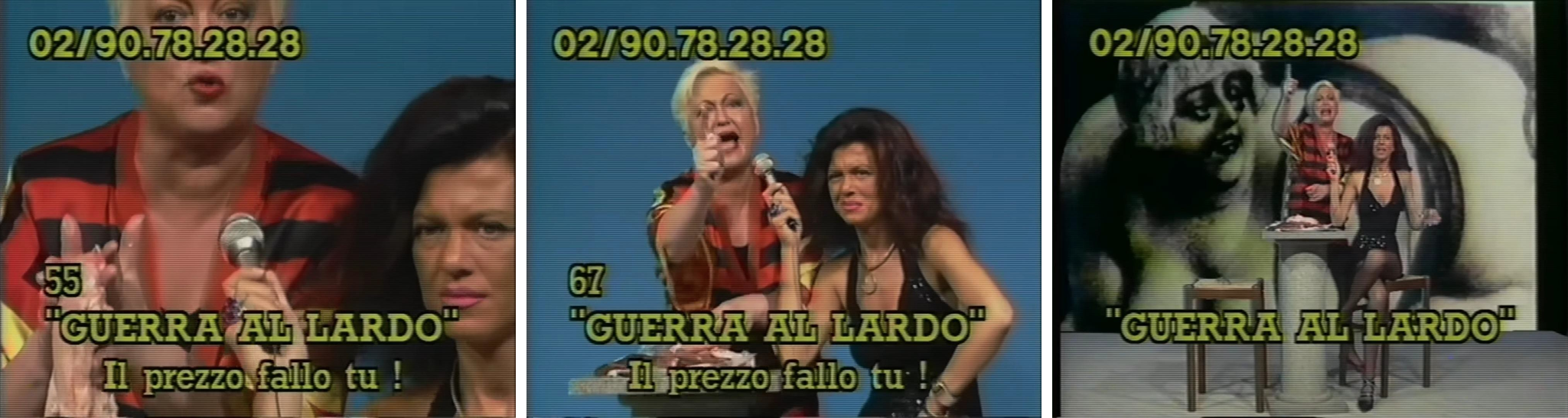

I now turn to three consecutive frames from one of their broadcasts (figure 3). I was fifteen years old when this clip resurfaced online and quickly went viral, transformed into a meme circulated for its perceived absurdity. While many found it humorous, others—myself included—experienced it differently. For me, this was a choreography of humiliation.

Figures 3. Wanna Marchi and Stefania Nobile in a televised segment declaring guerra al lardo—“war on lard” (stills taken from the Fremantle/Netflix docuseries Wanna, 2022).

The still on the left-hand side captures Marchi gripping a slab of raw meat. In the preceding footage, she is seen cutting and slapping it while loudly comparing it to human body fat. She shouts into a microphone held by Nobile, who is silent in the this first frame, nearly laughing in the middle one, and finally screaming alongside her mother on the right-hand side. Nobile wears a tight black dress that accentuates her slim body—an avowed visual contrast to the problem they claim to solve. In two of the stills, the meat lies on the table like a sacrificial offering. Marchi points at the viewer, then at the sky, her arms slicing through the air. Behind them, in the right-hand-side frame, looms a black-and-white image of a plus-size woman, visually dominating the set; her expression appears sombre, adding an emotional weight to the scene. Text banners flash across the screen: guerra al lardo (“war on lard”) and a call-in number. “Fat women, … I want to help you! … I love you!” Marchi proclaims, before both women erupt into battle cries: “Let’s make war on lard! Call us!” Their eyes lock on the camera. The connotation is stark: fat becomes the enemy. War metaphors recast weight loss as civic and moral duty, while the pointed finger evokes command. Marchi’s declaration of love rings hollow amid the shouting, insults, and the militarized slogan. These images reveal how their care and cruelty collided in forms of psychological, economic, and interpersonal violence.

Marchi and Nobile’s images included manifestations of psychological violence (intimidation), economic violence (exploitation of insecurity for profit), and interpersonal violence (transmitted through mass media into the intimate space of the home). Their violence was verbal, visual, and emotional—disguised as care and empowerment. This not only aligns with Galtung’s typology I mentioned above but also extends it: their power lay in crafting of offensive televised images that weaponized emotions, intimacy, and sincerity. Emotions stick and move between bodies and signs, shaping social relationships and power structures. In the case of Marchi and Nobile, we observe how shame and disgust were mobilized through images, slogans, and gestures that equated “fatness” with failure and beauty with moral value. They did not merely communicate offence: they weaponised it. Offensiveness became the hook: if it made viewers feel something—if it hurt—it was working.

Christoph Baumgartner’s theory of offensive images provides insight into this dynamic. Offence, he argues, emerges when a norm is violated, triggering discomfort. This constituted the initial element that facilitated emotional manipulation. Marchi and Nobile’s offence lay in their rupture with conventional codes of televised femininity. Guerra al lardo (“war on lard”) was not simply a slogan, but a televised performance of humiliation that militarized the female body and cast fatness as a moral and aesthetic threat. Their ambiguity—were they saviours, saleswomen, or bullies?—destabilized viewers’ moral reception. The violation was not only in their disruption of decorum in commercial speech but in the ethical disorientation it caused: violence was framed as help, love as aggression. This generated a troubling ethical dissonance that viewers were compelled to internalize, resolve, or resist—often without the critical tools to do so.

The manipulation relied on vulnerability. Consider the below excerpts from an interview with Marchi and Nobile featured in the recent Netflix series about them:

You want to know how far you can go in exploiting people’s weaknesses? We’re all weak. We all need illusions in life. Idiots need to get fucked! … If someone sells you a device and tells you that if you hang upside down by your feet, he will make you grow five centimetres taller, and you actually hang upside down, is he a scammer, or are you an idiot?

This logic flips vulnerability into fault. If you fall for it, you deserve it. These attitudes collapse into a coherent strategy: turn emotions, humiliation, and weakness into profit. What is at work here is psychological, economic, and interpersonal violence as not simply an unfortunate by-product but rather as the business model itself.

Marchi and Nobile blurred the line between sales pitch and soap opera, weaponizing theatrical intimacy. Through tight camera framing, sustained direct eye contact, and minimal ambient sound, they crafted an illusion of proximity. Their tone fluctuated between tenderness and aggression, addressing viewers as cara and tesoro (“darling,” “sweetheart”), even while scolding or shaming them. What they sold was recognition—the viewer was seen, addressed, judged, and then offered the promise of rescue.

Images are not passive representations; they possess agency, act, and do things. Marchi and Nobile’s televisuality performed, seduced, humiliated, commanded. Their images demanded submission, belief, and purchase. This performative dynamic was reinforced by the set design: bare, low-budget interiors free of visual distractions and suggestive of familiarity and authenticity. Frequently, the product itself was not shown—the duo’s performance was enough to distinguish their ads from competitors. The minimalism of the mise-en-scène of this invasive choreography invited participation. Because it felt personal, many did not resist. The offensive screamed insult masked as intimate care intensified the power of the image.

Sincerity was crucial to Marchi and Nobile’s strategy. “A fat is called fat, a thin is called thin. … Not offensive, we were realistic … Are they beautiful? … We put them in front of the mirror,” Nobile declared in an interview. Marchi echoed that the insult strategy worked “because it is truth.” This appeal to sincerity resonates with anthropologist Jojada Verrips’s definition of offensive imagery as visual expressions that disrupt shared moral or aesthetic expectations, provoking visceral reactions by transgressing perceived boundaries. Marchi and Nobile did not merely offend—they claimed to reveal. Cruelty was recast as realism, violence as honesty. They spectacularly transformed private insecurities into public accusations that contradicted norms of politeness, dignity, and respect—an aggressive exposure of what society urges individuals to conceal. The offence derived its power from emotional engagement while being rhetorically disarmed through appeals to honesty or concern.

Conclusion

By shouting beauty promises and by marketing violence as salvation within a system that turns insecurity into spectacle, Marchi and Nobile manifested the violence ingrained in advertising itself: the sale of our own insecurities back to us under the illusion of self-transformation. An in-depth discussion of this teleshopping duo is timely because their practice—long treated in Italy as a footnote to media folklore—anticipates contemporary forms of affective and algorithmic persuasion. What initially appeared as the excesses of daytime television was in fact a precursor to the more discreet yet pervasive pressures of today’s visual economy where promotional messages permeate the intimate rhythms of everyday life, infiltrate our pockets through influencers who seamlessly merge personal narrative with commercial address. Contemporary advertising mobilizes dynamics similar to Marchi and Nobile’s albeit in smoother and more platform-friendly forms. The turning of insecurity, aspiration, and relational dependence into leverage on screen persists today across social media, where glow-up tutorials, wellness scripts, and affective appeals rehearse the same gendered demands for transformation. Both then and now, spectatorship itself is disciplined: through not simply what is shown but rather the emotional regimes that structure how viewers feel, desire, and self-regulate.

Wanna Marchi and Stefania Nobile in a televised segment declaring guerra al lardo—“war on lard” (stills taken from the Fremantle/Netflix docuseries Wanna, 2022).

Chiara Pecorelli is an Italian scholar pursuing a master’s degree in Visual Culture at Lund University. Her research interests focus on the intersections of the body, food cultures, and representation with an emphasis on how cultural practices shape embodied experience. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Industrial Design, where she examined design as a tool for care and social engagement through community-based and participatory projects.

Chiara Pecorelli, “Selling beauty and violence on Italian daytime television” JVC Magazine, 3 December 2025, https://journalofvisualculture.org/selling-beauty-and-violence-on-italian-daytime-television/.