Images of the Mexican landscape tend to teem with expansive skies, jagged mountains, vast agave fields, and dramatic clouds. This imagery, immortalized by the work of Gabriel Figueroa during Mexico’s Golden Age of Cinema (1930s–1950s), is a powerful symbol of national identity. His cinematography created the image of the mythical Mexico as a land of resilience and grandeur, shaping the defining aesthetic of Mexican identity.

Nearly a century later, Mitzi Falcón both inherits and subverts this tradition. In her photographic series Endhó: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Falcón utilizes formal techniques reminiscent of Figueroa’s—dramatic contrasts, expansive compositions, and atmospheric skies. However, where Figueroa’s landscapes celebrated Mexico’s resilience and natural richness, Falcón’s images reveal environmental ruin, using the landscape’s beauty first to lure and then to reveal the ravages of industrialization.

As a medium, landscape has a long history of entwinement with power, with national identity as articulated especially through notions of the sublime, and with environmental violence. Placing Falcón’s work in a conversation with theorizations of these entwinements helps understand precisely how she defies Figueroa’s ideological imagery.

First, some background on Figueroa himself: Gabriel Figueroa was born in Mexico City in 1907, at the tail end of the Porfirian regime, a time marked by social injustices and modernization. This period was followed by the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution. It was up to Figueroa’s generation to develop a new identity for the nation. With a career of over 200 films, his exaltation of the countryside became synonymous with national strength and perseverance. His distinctive formal techniques made up of high contrasts, wide-angle compositions, and his expertly use of the chiaroscuro influenced by the European Baroque masters framed Mexico in a timeless and grandiose fashion. Figueroa captured the sublime by following the European Romantic tradition, which framed landscapes—exceedingly vast, untamed wildernesses—as spaces that evoked fear and awe. Kant distinguished the sublime from beauty, arguing that the sublime “is to be found in a formless object” and represents “boundlessness.” Figueroa captured this boundlessness in nature by using a diminishing glass to convert a 25 mm lens to 20 mm for shooting landscapes. This created a curvilinear effect that bent the horizon line, producing a more organic feeling that emphasized the depth and expansiveness of the sky. This manipulation mythologized the land and presented a romantic tableau of Mexico that stood in stark contrast to the country’s rapid industrialization. Figueroa’s aesthetic innovations were not just technical choices; they participated in the reconstruction of national identity through landscape as has been the case in several other postcolonial contexts. The post-revolutionary Mexican art movement attempted to create a unified national identity through aesthetic synthesis, blending Indigenous and European traditions. However, as Néstor García Cancilini argues, the problem with this attempted synthesis was that the artists involved were often caught up in the complex contradictions that characterized modernization and cultural hegemonization (e.g., those involving promoting Indigenous heritage while adopting Western models of development, or celebrating rural life while actively contributing to its marginalization through urbanization). Figueroa attempted to solve these contradictions by turning to unspoiled rural landscapes against eroding urban modernity, portraying the marginalized communities in both settings as struggling but always dignified.

Both Denis Cosgrove and W.J.T. Mitchell critique the aestheticization of nature that serves identity formation. Cosgrove noted that while Romantic sublime landscapes seemed to challenge industrial capitalism they ultimately “mystified implications for land and human life.”[1] It mystified them by erasing the labour and the histories embedded in landscapes, reducing them to mere visual spectacles. Mitchell describes the landscape as “an instrument of cultural power” that “naturalizes a cultural and social construction.”[2] These representations of rural landscapes as pristine and untouched erase the histories of colonization and environmental exploitation.

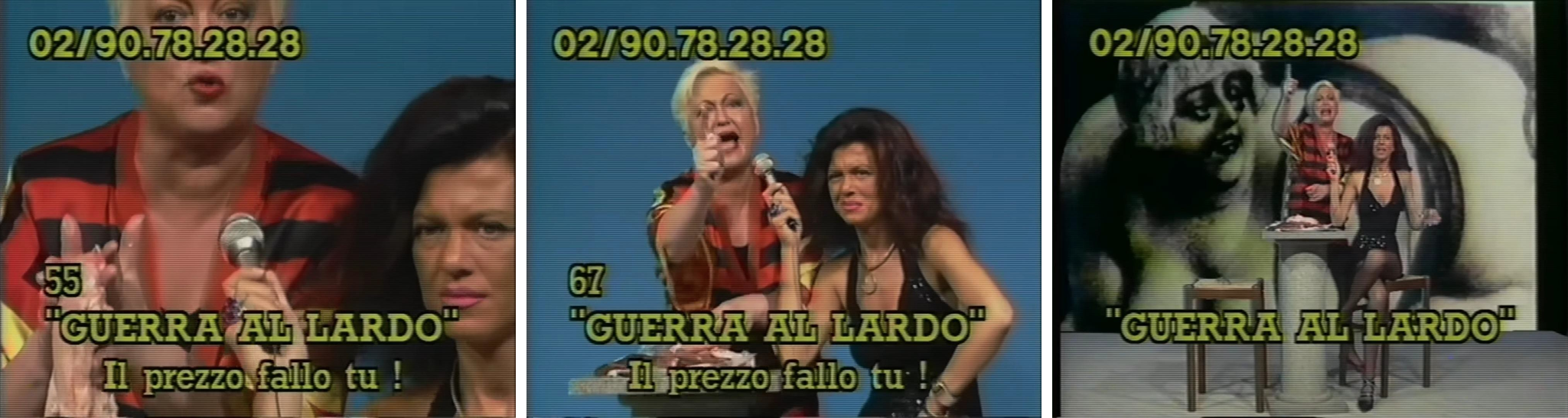

Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Trabajador presa Endhó, 2024, Digital photography.

If, as Mitchell argues, landscape often serves ideological power, Falcón reclaims it as a site of grief and testimony. She is motivated not by nationalism but by her biographical connection to the land and by embodied experiences of suffering under environmental collapse. Her work is informed by collective memory, community resilience, and grassroots connection. Instead of mythologizing the land like Figueroa, she pries open the wounds of postmodernity. Her work resonates with Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of “the right to look,” as it challenges the traditional authority of visual culture in shaping narratives of identity and power. Mirzoeff: “the right to look claims autonomy, no individualism or voyeurism, but the claim to a political subjectivity and collectivity.”[3] Such claims reverberate across Falcón’s work as it demands a critical re-evaluation of how landscapes are represented and who has the agency to define their meaning.

Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Espuma de tensioactivos a la orilla del río, 2024, Digital photography.

Consider Falcón’s essayistic photography series Endhó. It documents the transformation of the Endhó dam in Tepetitlán, Hidalgo, a body of water that was once considered a paradise but is now listed among the most polluted sites in the Americas. Falcón’s images deceive at first glance with their dramatic skies (figure 1), ethereal clouds touching the ground (figure 2), and sweeping landscapes (figure 3) that all recall the sublime grandeur of Figueroa’s images. However, upon closer examination, the clouds that appear to be touching the ground are, in fact, highly toxic chemical foams emitting from polluted dam water. Their surreal stillness underscores a grave reality.

Figure 3. Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Espuma de tensioactivos en cultivos de maíz, 2024, Digital photography.

Falcón’s photographs do not immediately disclose ecological disaster. At first glance, the waters appear ethereal, their surface cloaked in foam-like clouds that seem to touch the sky. This deliberate ambiguity echoes Figueroa’s sublime vision. Yet, where his landscapes evoked pride in the nation’s resilience, Falcón’s images elicit sorrow and unease. Here the sublime beauty is an accomplice in the devastation.

The Endhó Dam is at the heart of a terrifying case of environmental devastation. The irreversible effect of the residual waters coming from Mexico City and the State of Mexico has not only altered the ecosystem but also taken lives, with the local community paying the price of capitalist industries and petroleum refineries. These waters contain a toxic mix of substances—including butanediol, nitrates, and heavy metals like cadmium, lead, and zinc—that exceed safe levels and have contaminated soils, crops, and groundwater.[4] These substances choke the water of oxygen, slowly killing off fish and other aquatic life. In their place, invasive plants like water lilies have taken over, blocking sunlight and turning the dam into a stagnant swamp. This dark, still water has become the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, especially Culex, which carry diseases like dengue, yellow fever, and encephalitis. In desperation, residents have turned to using gasoline and banned chemicals like DDT to fight the infestation—measures that end up harming their own health, exposing them to long-term risks like cancer and hormonal disorders. It is a cycle of contamination and survival, where the community is left to deal with the consequences of decisions made far from their homes.

Falcón confronts this violence head on. For her, environmental devastation and the sublime are interlocked. Burke describes the sublime as “delightful when we have an idea of pain and danger, without being actually in such circumstances; this delight I have not called pleasure, because it turns on pain, and because it is different enough from any idea of positive pleasure.” Through her high-contrast black-and-white images, Falcón portrays environmental devastation as a sublime whose sublimity is due to the viewer’s distance from the toxic waters (figure 4). This decay is what Robert Nixon calls slow violence, “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”[5] Capturing slow violence is difficult, but Falcón succeeds in this task by forcing recognition of a pollution that often goes unnoticed.

Figure 4. Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Canal de aguas negras, 2024, Digital photography.

While Figueroa uses the landscape as a medium to glorify the land, presenting it as a symbol of national strength, Falcón confronts the viewer with loss. In her work, the sublime is the subject of not awe, but mourning.

Endhó is personal, too. For Falcón, is not only a site of ecological concern but of a deep biographical wound as her family’s house stood a mere 18 meters from one of the canals that feed the dam (figure 5). The contamination seeped into their lives, poisoning everything around them. It is a space intertwined with grief—grief for her childhood, for the land itself, and for her grandmother, who chose to end her own life there. This land no longer offers the idyllic refuge that it used to for previous generations. It has become a repository of trauma.

Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Puente a casa de abuela Cirila, 2024, Digital photography.

Falcón’s intimate connection with the toxic waters renders Endhó more than a visual lament; the work becomes an act of resistance. Where Figueroa once constructed a legendary Mexico to inspire nationalist admiration, Falcón exposes its ruins to demand accountability from the government. Nixon: “one of the most pressing challenges of our age is how to adjust our rapidly eroding attention spans to the slow erosions of environmental justice.”[6] Rather than offering nostalgic comfort, Falcón’s images index the urgency of repairing systemically marginalized lives that continue to be disproportionately affected by the slow violence of capitalism.

The visual dialogue between Figueroa and Falcón encapsulates shifting interpretations of the Mexican landscape throughout the past century. For Figueroa, this landscape was the stuff of an identity-building cinematic dream. The sublime countryside romanticized the nationalistic vision and unified post-revolutionary Mexico. Falcón, on the other hand, contests this vision of landscape and grieves the nightmare that it has become (figure 6).

Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Espuma y fango de tensioactivos, 2024, Digital photography.

Both artists share a visual language of dramatic contrasts and reverence for the resilience of countryside communities conveyed through the concept of the sublime. Nonetheless, the messages that each artist transmits to the viewer diverge sharply. Figueroa erected a myth of Mexico through a romantic vision of the sublime as this untouched, boundless, rich land that was so vast it overwhelmed our faculties, thus tending to ignore the history of violence and colonization. Falcón confronts the scars left by the industrialization of the twentieth century through a version of the sublime linked to a terror and danger. Figueroa’s landscapes invite admiration, while Falcón’s invite unease, as their beauty is poisonous.

The landscape is not a neutral backdrop but a site of power, history, and struggle. From the Romantic sublime to the contemporary ecological crisis, representations of landscape shape and reflect broader ideological and political realities. By engaging with theories of the sublime, environmental violence, and decolonial aesthetics, Falcón’s Endhó uncovers hidden narratives embedded within landscape imagery and challenges the structures that sustain them. The work invites the viewer to confront them as a beautiful tragedy that should not be ignored. It presents the dam as a wound and a mirror, reflecting the consequences of industrialization, but also as an opportunity for healing. Perhaps one day, the clouds will no longer hover toxically over the dam and will reclaim their place in the sky, reflecting upon waters restored to their erstwhile clarity. Falcón’s work calls for action, urging us to confront the environmental violence of today to ensure that the landscape is not reduced to a ruinous archive of industrial exploitation.

The Mexican landscape has long been a myth-making site. Figueroa is one of the most prominent figures to define it, while Falcón exposes its contemporary decay. Considering their work together helps reflect on the tension between beauty and destruction, nationalism and abandonment, cancelled dreams and the present crisis. Falcón’s version of the sublime reminds us that environmental violence is not a distant crisis; it is fully embedded in our landscapes. What we see (or fail to) determines whether this violence continues unchecked. As Mexico’s landscapes continue to transform under capitalist industrial and environmental pressures, how will they be portrayed? These portrayals shape our awareness and responses to environmental violence. The task, perhaps, is to redefine the myth of the land in a way that facilitates the political work of repair, restitution, and restoration rather than simply documenting the ruins produced by the violence.

[1] Denis Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), p.234.

[2] W. J. T. Mitchell, Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), p.2.

[3] Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), p.1.

[4] Comisión Nacional del Agua (Conagua), Indicadores de calidad del agua en la cuenca del río Tula-Endhó (México: Conagua, 2018)

[5] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), p.3.

[6] Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, p.8.

Mitzi Falcón, ENDHÓ: Cuando las nubes tocaron el suelo, Canal de aguas negras, 2024, Digital photography.

Sofía Sánchez Borboa is an art historian and curator focusing on questions of identity, representation, and cultural history in contemporary art. Her work critically engages with democratization of access to art, exploring its social and cultural implications. Recent projects include the exhibition Spaces We Inhabit at Hope College (2025), and the book Memoria de Coyoacán: Quien nunca se ha aburrido, no puede ser un contador de historias, a fragmentary narrative of her neighborhood. Her curatorial and scholarly practice is grounded in a commitment to fostering dialogue and critical reflection within the contemporary art world.

Sofía Sánchez Borboa, “Ruins of the sublime,” JVC Magazine, 18 May 2025, https://journalofvisualculture.org/ruins-of-the-sublime.