Øyvind Vågnes (1972–2025)

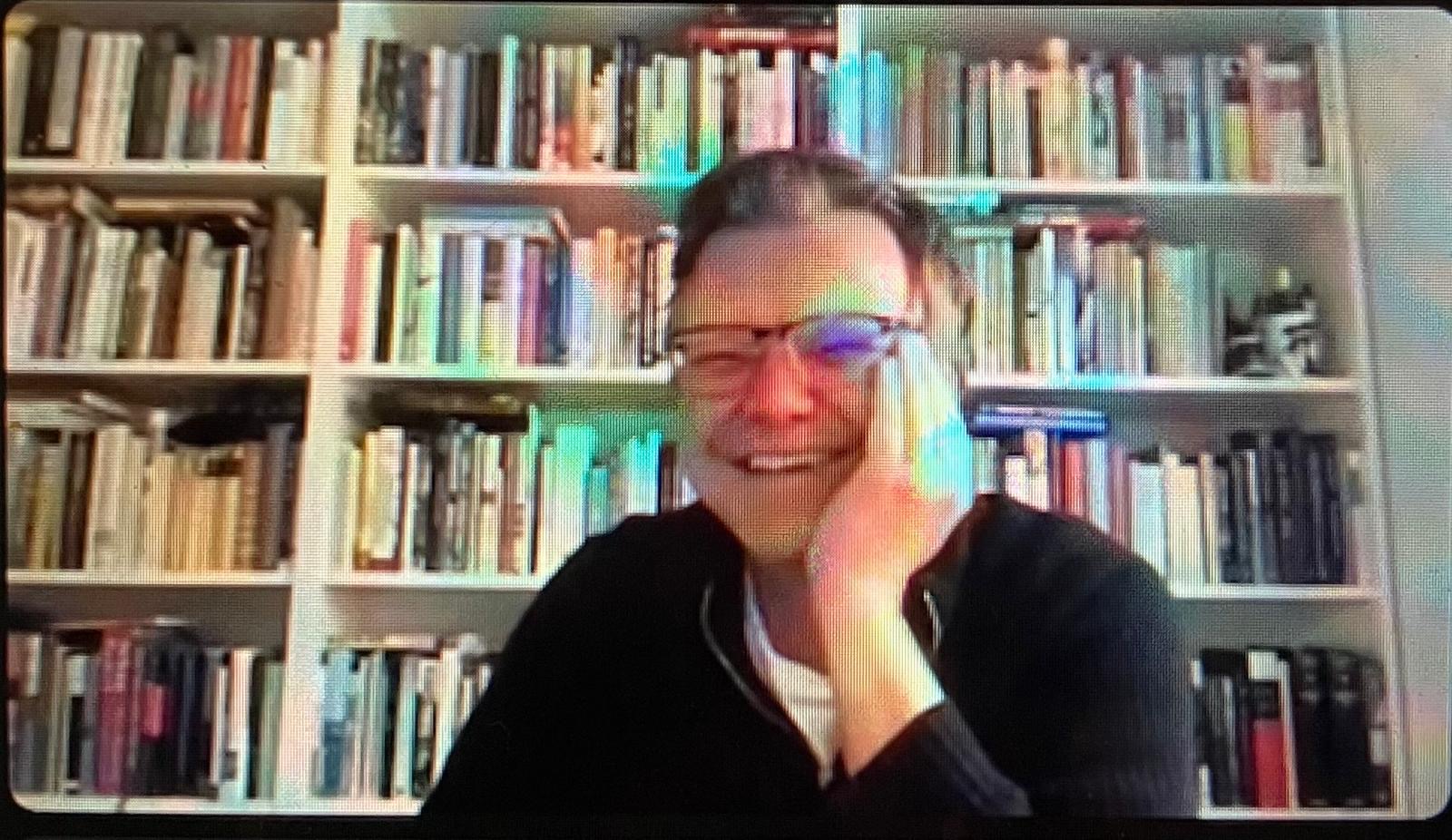

It is with profound sadness that we must acknowledge the passing of Professor Øyvind Vågnes after a short illness. Although he only lived to be 52 years old, within the short time span of his life, he was able to accomplish enough to fill several academic careers.

It is not just the University of Bergen or the Norwegian academe that have lost one of their most brilliant professors. Early on, Øyvind placed himself in the top-tier of his field internationally, and condolences from a global network of researchers have poured in. Now, our thoughts go to the closest family, his wife, Birgit, and their two sons, Eskil and Amund, both of whom Øyvind was immensely proud.

Øyvind grew up in Brattvåg, a small place on the West coast of Norway, and arrived at UiB as a student in 1992, where he studied Comparative Literature, Nordic Language and Literature, and took his postgraduate degree in English.

I first met Øyvind on an evening in June in 1997, in a student bedsit on Nygårdshøyden, close to campus. In the early 2000s we were both PhD-fellows at the English Department at UiB where we were part of what I would venture to designate a golden generation of researchers on English literature, which consisted of, in addition to Øyvind and myself, Lene Johannessen, Michael Prince, Ruben Moi, Janne Stigen Drangsholt, and Charley Armstrong, all of whom are prominent professors at various universities today.

Øyvind started work on his PhD-degree at the English Department in 2002, with the grand old man of American studies, Orm Øverland, as his supervisor. In 2007 he defended a dissertation that traces the journey of the infamous Zapruder-film and its effect on the world’s collective imagination in an aesthetic and popcultural context. A few years later, in 2011, this academic work was published by the renowned University of Texas Press, under the title Zaprudered: The Kennedy Assassination Film in Visual Culture. For this publication Øyvind was not only awarded the prestigious Peter C. Rollins Book Award, but was also one of three nominees for the American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly Excellence.

During the work on his dissertation, he also received a Fulbright Fellowship at Georgetown University in Washington DC, where he arrived only days prior to the 11 September attacks. I think this experience influenced his academic work to a stronger degree than even he himself was aware.

In the years after the millennium, Øyvind and I became inseparable, both as friends and colleagues, and in 2005, when I moved to the newly established Department of Information Science and Media Studies at Faculty of Social Sciences, he naturally came along. The scholarly and peer-reviewed journal Nordic Journal for Visual Culture (Norwegian title: Ekfrase: Nordisk tidsskrift for visuell kultur) was conceived at a simple impulse, over a glass at Café Opera. The first issue was published by Scandinavian University Press (Universitetsforlaget) during the autumn of 2010, with a resplendent launch-party at Copenhagen University.

Øyvind’s contributions to a myriad of newspapers and journals were exhaustive. In addition to the Nordic Journal of Visual Culture, he was associated with the student newspaper, Studvest; the journal for culture and literature, Vagant; and, from 2018 and up until the present time, the renowned Journal of Visual Culture.

In 2008 – the same year that we both became fathers for the second time – we co-founded Nomadikon: The Bergen Centre of Visual Culture. Then, up until 2012, Øyvind was a postdoctoral fellow on the project Nomadikon: New Ecologies of the Image, managed by myself and financed by what is today known as Trond Mohn Research Foundation. As in every context, Øyvind was a central driving force in this project. In addition to the many academic publications that were produced, we were also responsible for more than a dozen conferences, many of which were held abroad.

In 2015, Øyvind achieved tenure in Media Studies, and from 2018 was Full Professor. From 2017 up until the present time, he was instrumental in building a highly successful study program in film- and television-production at Media City Bergen, where he was responsible for a flourishing postgraduate course in screenwriting for television series.

Øyvind was an exceptionally productive scholar. Articles and conference papers kept coming at a fast pace.

In 2014 he published the seminal book Den dokumentariske teikneserien at Scandinavian University Press (Universitetsforlaget), which explored documentary graphic novels by artists such as Joe Sacco and Alison Bechdel. Together, we published a wide range of academic anthologies: In 2010 Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics (The University of Chicago Press) was published, and, in 2016, we produced Gestures of Seeing in Film, Video and Drawing (Routledge), edited with our close friend Henrik Gustafsson, while in 2019 we published Invisibility in Visual and Material Culture (Palgrave Macmillan).

Even during his time in the intensive care unit at Haukeland University Hospital, an article with his name on the cover was published. Over the Christmas holiday, the journal American, British & Canadian Studies printed the article “The River in Reverse: Flood Imaginaries, Old and New”. Before Øyvind fell ill, we had started – and here I had to stop to count – five quite variegated book projects together.

Øyvind managed the research group for Film, Television, and Visual Culture at the Department of Information Science and Media Studies (together with our good colleague Anders Lysne and myself), and Øyvind and I were also active members of the research group Aesthetic and Cultural Studies at the Department of Foreign Languages, as well as the Contemporary Aesthetics Research Group at the Department of Linguistic, Literary, and Aesthetic Studies.

Øyvind was not just an academic scholar, however. He was just as formidable in two other fields – fiction and criticism.

In 2003, his debut novel Ingen skal sove i natt was published on Tiden Norsk Forlag, a work that was characterised by a highly developed sense of style and voice. This was followed by the equally impressive Ekko in 2005. (I still remember reading this while sitting at the café Jolly Joker, located by Nieuwmarkt in Amsterdam, that same spring.)

For each published novel it became abundantly clear that Øyvind was not planning on staying within the framework of one definitive style; his literary range was just as diverse as his academic interests. Sekundet før (2010) can in many ways be seen as the fictional aspect of the research questions he was working on at the same time. Sone Z (2014) is a linguistically stripped novel which thematises surveillance and the use of drones, while Vesaas (2017) investigates the space between satire and aesthetic theory. On occasion, he would talk about the writing process; I remember a moment in 2021 when we were crossing the Seine at Pont au Change and he shared a glimpse of the plot of the complex multigenerational novel Ei verd utan hestar (2022).

Øyvind was also a highly respected critic in the Norwegian cultural newspapers Klassekampen and Morgenbladet. For many years he worked as a music critic for the weekly paper Dag og Tid, and I have learned from several sources that many regarded him as the leading national rock critic. Here, I can add that at least one of the most prominent contemporary American music critics was full of admiration for Øyvind. All in all, I think music was Øyvind’s greatest passion, and it is heartbreaking to realise that he will not be allowed to develop the many book projects that he had envisioned in this field.

The time has now come to thank him for being a part of this journey – the best companion anyone could possibly have had, and I mean that both figuratively and literally. During the time that we had together, we travelled for work to London, Rome, Copenhagen, New York (several times), Athens, Winnipeg, Rio, Los Angeles, Toronto, San Francisco, Berkeley, Paris (many times), Rethymnon, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Nashville, Albany, Muscle Shoals, and Macon . . . and these are only the places I can think of off the top of my head! Every journey was filled with joy, even that time when we got lost in Rio’s favela, just a few days before my own wedding, where he was best man.

Øyvind has left a deep imprint on the Norwegian cultural scene as well as in the academe.

There aren’t many about whom this can be said, but absolutely everything he touched turned to gold. In spite of this, he was not at all focussed on his career. Instead, his attention was directed towards people. The warmth and empathy that he met others with is something that I think we can all learn from. I have been lucky enough to witness this first hand, and I think his approach has been of vital importance, especially in encounters with students and young researchers.

In Øyvind’s presence everyone immediately felt welcome and appreciated. He was also great at building environments – wherever he went, things instantly began to sprout and grow. No wonder he ended up with such an enormous network of friends and colleagues. Øyvind was the incarnation of a culturally, aesthetically and ethically formed human being. Or, as many have expressed on Facebook: Øyvind was good – simply good.

To lose such a dear friend and colleague is a transformative experience. I am already a different man than I was before 7 January this year. The final conversation between us concerned, among other things, the poem “Anecdote of the Jar” by Wallace Stevens. When I told my wife Stephanie about this, she simply said “of course, that is the two of you”.

Forever irreplaceable Øyvind, we will miss you always.

Translated by Janne Stigen Drangsholt, Professor of English Literature at the Department of Cultural Studies and Languages

Asbjørn Grønstad is Professor of Visual Culture at the Department of Information and Media Science, University of Bergen.