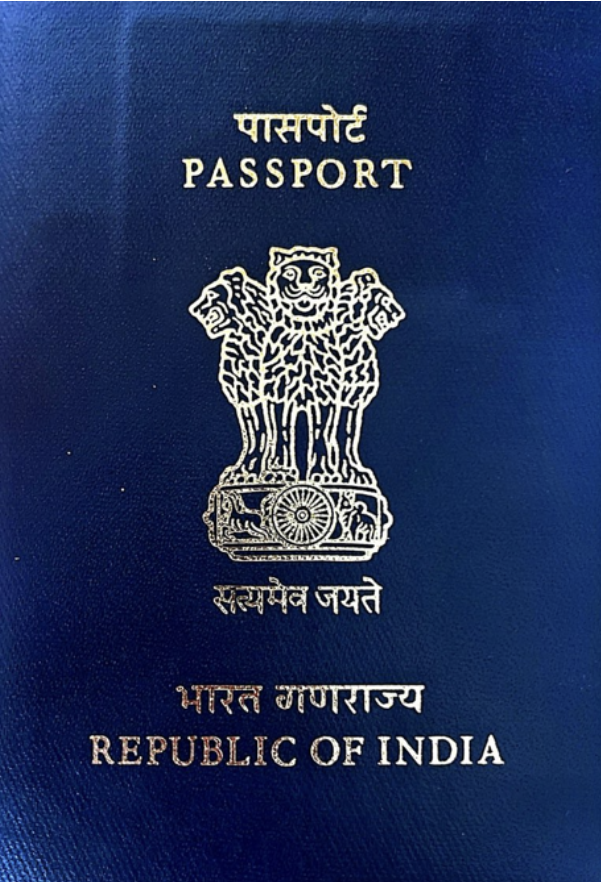

When I recently stumbled upon my first passport (figure 1), it triggered contradictory feelings in me. I looked at it with a sense of strangeness, as if it didn’t fully belong to me, and yet it was as much a part of me as any piece of clothing or accessory. In the most literal sense, it’s a small, lightweight object, and easy to carry. But, on a deeper level, it’s vital for social and national identification—sort of like an outfit which impacts how we are perceived. In what follows I reflect on my dual identity as a Spaniard asking what it would have meant to continue using my Indian passport. Passports serve as something of a pre-border before one’s encounter with actual state borders. Since visas function as permits to travel to intended destinations, passports limit individuals even before they embark on their journeys. As “paper prisons,” passports confine individuals to national boundaries—akin to being imprisoned within physical cages—largely determined by the circumstances of their birth.

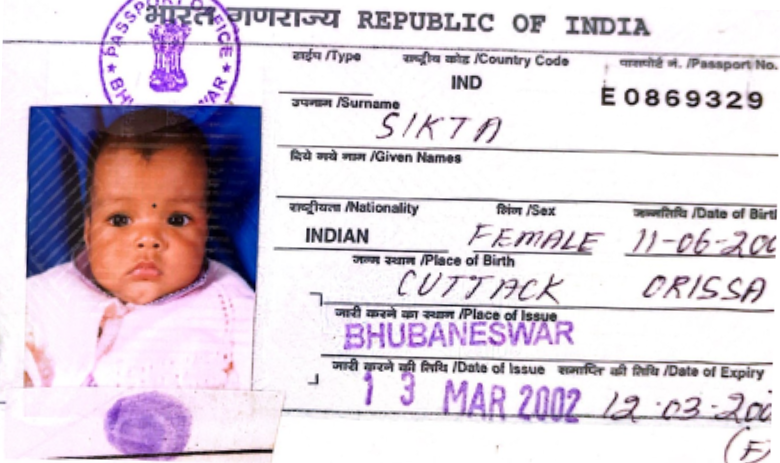

Figure 1. Cover of Paula Sikta’s passport issued by the Indian authorities in 2002 and valid until 2007.

My first passport lies in a box alongside other objects that have formed parts of my past and that, whether I like it or not, belong to me. This accumulation of documents and memories is the stuff of an archaeology of memory, a vast archive in Derridean terms. I see this archive as a way of fixing our existence in time, a means of ensuring that parts of our identities are not forgotten.

Even though I knew this passport existed, I had never considered looking for it—not out of fear or confusion but due to the arduous and complex nature of archival work. Gradually, my interest in nationality, identity, and borders —recurring themes in my research—led me to it. Passports are similar to maps in that they serve as political symbols transcending their geographic function and ultimately as instruments of colonial control. Reflecting in this vein on nationality, diplomacy, and politics, I remembered that I was not born in the place where I’ve lived most of my life. Physical displacement—whether as a migrant or, in my case, as an adopted child—has been amply debated for the marginalization it causes. Yet it is rarely considered for its mundane, bureaucratic implications. Identity papers create a parallel universe to the real one. Many people suffer the stress of poor bureaucratic management, left without valid representation beyond the borders encircling their homes. The link between documentation and identity may seem obvious and a passport may just seem to be a piece of paper. But many feel completely bound by it. My recent reencounter with mine revealed to me a hitherto unknown fact: I didn’t obtain Spanish nationality until I was three years old. And yet, I was already Spanish. Maybe I was also—and still am—Indian.

Finding my passport in a box full of objects meant more than a simple discovery. It seemed to be woven into the network of “vibrant matter” stored there as if it had a life of its own. In the box were documents about my adoption, printed emails, and other mementos like tiny bracelets or pieces of clothing (figure 2). If you looked at the box from the outside, it wouldn’t seem special at all: just a cardboard box with a label reading “Paula’s Things.” But what does it mean for something to be “mine”? Some of these “Paula’s things” were created and handled by others before me: emails exchanged between my parents and the orphanage, and documents that mention my name but that I never wrote or read. These things were not just mine; they also belonged to others. This personal archive was built carefully by my parents—a box that, perhaps unintentionally, imbues the objects in it with agency. I’ve scanned some of the documents and items I found meaningful to accompany this essay. I’ve catalogued them as if they were archival materials, naming them and numbering them (figure 3).

Out of all the objects in the box, why did I choose the passport? I think passports, alongside their bureaucratic function, are visually charged. They display the symbols of a nation: its coat of arms, language, and cultural references. I look at my Indian passport with a sense of distance. I can barely recognize the symbols on it, except for a few images of Gandhi found on pages reserved for stamps and visas. The Hindi letters are unreadable to me; I’ve only learned to recognize the letter N in “Name.”

My passport is special in another way: it’s handwritten, I don’t know whether it’s because of when it was issued (2001) or a lack of resources. But this detail gives the document a unique quality. Someone, at some point, wrote on it in their own handwriting, making it an object marked by time. Their trace adds to mine: my tiny fingerprint taped to the passport—something that makes it even more a part of me (figure 4). My first passport was issued for a single purpose: to allow me to leave India and arrive in Spain. I would never use it again as an identity document. Passports reshape our identities for presenting us to international bureaucracy. But what happens when there are missing pieces in one’s identity? In my case, they were invented: I had no last name, no known origin, no acknowledged parents—but all of this information was required for the document. Someone decided to construct my original identity randomly. It amuses me to think that I was invented. But I’m also grateful that they did it. After all, every child is granted an identity from the get-go; in my case, there were just some missing pieces to do it the usual way.

Figure 4. Identification page from Paula Sikta’s passport issued by the Indian authorities in 2002 and valid until 2007.

This fact of invented identity reminded me of Venezuelan artist Ana Mosquera’s interactive installation Carnet to Go. It explores how identity is constructed, assigned, and manipulated in the context of bureaucracy, technology, and hypercapitalism. It introduces the concept of disposable, randomly assigned identities, and invites reflection on the arbitrariness of official identification systems, which becomes obvious in programs like the U.S. visa lottery. Visitors engage with the installation by tearing off flyers from the exhibition walls and scanning QR codes that connect them to a Telegram chatbot. There, they receive a randomly generated ID and a prediction of their future, offering them a personalized experience of bureaucratic randomness. A promotional video embedded in the installation highlights the seductive nature of convenience and efficiency in tech-driven systems, while subtly questioning the erosion of privacy and autonomy. Carnet to Go challenges audiences to rethink the ethics and mechanisms behind identity, control, and the role of chance in our increasingly data-driven societies.

When I share experiences and thoughts with other adoptees or migrants, the issue of bureaucracy always comes up: residence cards, valid passports for exiting and entering the country, and proper documentation. I find it perverse to categorize people by passports and identity papers, as if identity were a fixed and objective entity, when in fact it is a fluid process—a socially constructed web. The passport, like other identity documents, can be interpreted as a biopolitical mechanism, one that regulates people’s identities as well as their movements across borders. These documents don’t just certify who we say we are; they also construct a legally, politically, and socially accepted identity. Scholars of biopolitics such as Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben have shown that institutional measures and mechanisms regulating life serve to keep populations surveilled and under state control. Recent retheorizations of biopolitics in the context of bordering mechanisms have suggested that “paper borders” involved in visa regimes are the state’s first line of defence—a “borderism” that discriminates by essentializing the value of human beings. Current methods of migration control have favoured the emergence of forms of citizenship based on economic status, encouraging irregular immigration and networks of exploitation and mafia that capitalize on these irregularities, resulting in a necropolitics. “It is in the shadowy offices of embassies, far from the zoom of the media and the populist approach of political leaders, that a consequent border violence takes place. For it is here that the value and freedom of human beings are determined by their origin, condemning them to life and death journeys if they wish to redress this injustice and cannot afford to buy golden passports.”[1]

In navigating these questions around the necropolitics of passports, I turn to artists with dual papers like myself. Palestinian artist Emily Jacir’s work Where We Come From (2001–2003), for example, is a deep dive into narratives of identity and displacement, offering a poignant exploration of the Palestinian experience under Israeli occupation. Jacir used her American passport to take advantage of the mobility denied to most Palestinians. She asked fellow Palestinians, both within the occupied territories and the diaspora: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” The Palestinian passport becomes a clear example of identity void. Although the Palestinian Authority does issue passports, the lack of international recognition limits their symbolic and practical power. Jacir’s work shows that the Palestinian passport carries not only the imprint of displaced people but also the evidence of a nation without defined borders. How does a people construct their identity when international institutions do not validate their existence? The passport, beyond being a simple means of identification, becomes an act of resistance—a symbolic archive that, despite the barriers, persists as an affirmation of being and belonging. Yet, without universal acceptance, this passport also reflects the ongoing struggle for a recognition that is never fully granted, submerging Palestinians in a bureaucratic limbo that denies their existence in much of the world.

Does having held either an Indian passport or a Spanish one but not both simultaneously make me less Spanish or less Indian? I like to think of myself as a mix of both. In Western societies, it is difficult and sometimes impossible to be read as a full citizen. I’ve often been asked, “are you from here, like, really from here?” expecting me to share my whole life story. As a curator and researcher in the art world, I’ve noticed that most professionals in the contemporary artworld tend to view diversity as a box to tick when producing work and preparing exhibitions. I feel that the artworld is interested in me only when I speak about issues that are supposed to do with identity or my origins, as if I can’t talk about anything else. This is a fake interest that is often underpinned by racist attitudes and white self-congratulation. In fact, most racialized art professionals today enjoy similar levels of education and experience as their white peers and yet continue to be perceived as victims, fetishes, or quotas. As in the visa and passport processes, we are not allowed to construct our own discourse—it must always be shaped by or twisted towards white interests that perpetuate politics of inequality.

My archive begins with a document that I never chose. But in claiming its meaning, I choose to speak—to define and historicise myself. To exist among documents is to navigate between presence and absence, legality and fiction. But what if we claim this interstitial space as our own terrain?

It is time for migrant-racialised people to speak up—those of us who can. I do so by showing you both my passports. One says where I come from, the other where I am. Neither says where I belong. “Subjects have the right to define their own reality, establish their own identities and name their history.”[2]

[1] Henk van Houtum and Annelies van Uden, “The Birth of the Paper Prison: The Global Inequality Trap of Visa Borders,” en Rethinking the Biopolitical: Borders, Refugees, Mobilities…,” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40, no. 1 (2022): 25.

[2] bell hooks, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (Boston: South End Press, 1989), p.42

“Documents of Sikta,” photograph by the author, 2025.

Paula Sikta Maciñeiras Serrano is an art historian, curator and cultural manager raised in Madrid, Spain. Her work explores the intersections between memory, identity and representation. She has worked as curatorial assistant in the photography collections of the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (where she delved into visual narratives that challenge traditional power structures), collaborated with independent art spaces and collectives, and had curatorial residencies with institutions such as Salzburger Kuntsverein in Austria.

Paula Sikta Maciñeiras Serrano, “Nothing more than a passport,” JVC Magazine, 26 April 2025, https://journalofvisualculture.org/nothing-more-than-a-passport.