“This is not a strange land to me because we are all connected.” —Nemonte Nenquimo

“There are guns, and then there is thinking.” —Jacqueline Rose

Inseparability is planetary. Ancient wisdom may have recognised this inseparability but today I am seeing it in the saddest of ways, and that is the damage done to planet Earth and its people, from the cutting down of forests to the polluting of the seas and the wholesale destruction of communities. The planet is getting hotter and hotter, sea levels are rising, and habitats are being destroyed. It is heart breaking, yet what is to be seen, if not felt and directly experienced, is how one thing affects another, how everything affects everything and adds up to profound inseparability. It is hard to ignore what can only be called “affective life” and, moreover, that it happens across everything. It is also hard to ignore cries that are arising from all the damage done.

Listen to the cries. You know you can hear them. Wherever you are situated, you can hear them. For sure, some are actively saying “don’t believe your ears.” These are the ones disavowing not only the damage being done but also affective life. With all their might they want you to believe them, the lies. The disavowers sit there, picking off the wings of butterflies as their lies produce ever more oppression, sadness and pain in the world.

We are all responsible for each other. We are all responsible for the ills of the world. These words are blatantly asking each and every one of us to think. That is, to think ourselves and beyond ourselves. Most importantly, it is not to ignore the cries coming from the Earth, the forest, the animals and peoples, the seas and their creatures. Such thinking isn’t a blame-game, we are all involved. We are all responsible and it means that, without exception, we are all eligible to repair the damage and prevent more being done. But the thing is we are living in a world that wants us to take sides, and political parties haven’t helped. It seems no one wants you to think. Hatred, not thinking – let alone love – is on the rise and so too is a new regime of separation, inaugurated 20 January 2025.

The philosopher, activist and left-wing mystic Simon Weil wrote many words for public addresses – to politicians, religious leaders, students, farm workers, industrial workers – but these addresses often took forms that weren’t expected. For instance, when she was expected to speak on something concrete like trade union problems, she wrote the essay “Human Personality” in which we find an ethics of attentiveness and the spirit of justice.

Simone Weil had little faith in political parties. She wanted a political practice born of the abolition of political parties. In 1943, shortly before her death at 34 years old, she writes a short essay with those very words in the title “On the Abolition of All Political Parties.” With abolition in the title, it comes as no surprise that this essay finds little that is good with political parties – all political parties. Identifying the characteristics of political parties, Simone Weil says that the first objective and ultimate goal of any political party is “its own growth, without limit.”[1] When all is said and done, political parties are their own end. However, for Simone Weil, only goodness is an end. The “legitimate reason for preserving anything is its goodness.”[2]

When planet Earth, the habitats and inhabitants coexisting with it and because of it, exhibit all the signs of distress and harm, when reparation and making good are so very much needed, do we really need political parties making promises yet pitting themselves against each other and playing the worst games possible while pursuing their main objective, their own ends. Yet just that is happening today.

What is good about political parties, why keep them? In Simone Weil’s short essay, which would be one of her last, she says, “The mere fact that they exist is not in itself sufficient reason for us to preserve them.”[3] Political parties don’t want you to think; they want you to take sides. You choose, but that is not thinking. By 1943 World War II is turning towards its end and Simone Weil dismays that nearly everywhere no one is thinking, instead they are “merely taking sides: for or against.”[4] It is like a disease. It is killing us, and over 80 years later, more than ever, do we need to think.

Political parties don’t ask us to think. For Simone Weil it is tantamount to the intellectual oppression that was, for her, “historically introduced by the Catholic Church.”[5] From its beginning, the Catholic Church stifled thought and anyone who dared to think were threatened with ridicule and oppression, excommunication and expulsion. Today there are bullies – political bullies, religious bullies and rich bullies – that are continuing to do that. But some of these bullies are, contradictorily, peddlers of free speech. It is a contradiction that is akin to those words that are now on the lips of many to describe a wind that has gotten up on planet Earth: “libertarian authoritarianism.” As for free speech, there is nothing “free” about it. It doesn’t take long to work it out; when we speak whatever is said is situated, and in so many ways that we barely know. Thinking is, for starters, understanding that.

Can you imagine political parties ceasing to pit themselves against each other and, with that, the adversarial giving way to negotiation and a coming together to know. With the planet warming up by a sustained use of fossil fuels, the emission of greenhouse gases, the continual chopping down of forests and the eradication of communities, there needs to be an earthly coming together to know, think and find ways to act. We need planetary thinking and speaking.

The Cameroonian philosopher and political activist Achille Mbembe has been calling for a new planetary consciousness. In an interview given in early 2022, “How to Develop a Planetary Consciousness,” he speaks of exercising a capacity to know together, to generate knowledge together.[6] With respect to this capacity, he highlights the French word for knowledge connaissance as literally meaning “being born together.” We need to learn together how to inhabit the planet anew. And even though Mbembe recognizes the perhaps irreconcilability of the conflictive opinions and antagonistic positions found on planet Earth today, he believes it possible. It is here that we need to embrace the “infinite hope” that the activist Angela Davis called for at the 2025 Inauguration Peace Ball in Washington, D.C. “I want us all,” she said, “to generate the kind of collective hope that will usher us into a better future.”

For all the diversity of languages in our world, we need to find ways to speak together, to acknowledge and care for planetary inseparability. Diversity. Yes, let’s talk about diversity. In recent times it has come to be understood as a good thing as it has been realized that life – all of it, human and non-human alike – needs diversity to thrive. Diversity has been spoken of purposely and “practiced” to enable equity and inclusion. But some who walk this Earth would have diversity disposed of and practices of it rubbished. For all the sorrow this brings (it is not good), it does however prompt me to ask, how is difference to be thought of, and lived, with the planetary inseparability?

To protest “I am not like you” and assert “I am different” is a call for recognition. The difference calling out for recognition perhaps results from discrimination, denigration and woeful exclusion; yet acknowledging this difference can lead, almost inexorably, to the affirmation of an identity. And it is hard for identities to not enclose and separate themselves, even if only in the imaginary. The complication here can’t be denied. A “politics of difference” or a “politics of identity”? But either way what all too quickly slaps you in the face is separation.

So, how is difference to be thought of, and lived, with planetary inseparability? The question in no way denies – and it would be criminal to do so – the experience of being mistreated, humiliated, trodden on and “unrecognized,” which is indeed the miserable result of a humanity that is devoted to dividing itself, imposing regimes of separation and blind to inseparability. It is time to take a hard look at what acts of separation have done to not only human life but also all that is life; it is also time to understand a difference that neither is consequence of separation nor gives rise to it. There is such a difference. And how this difference arises is through the processes in which life “modifies” itself. Life can be such a baggy term; said so often yet, and sometimes almost stubbornly, remaining ill defined. But perhaps that is precisely it, that is if we agree that life doesn’t fit into a set of properties but is an activity.

Life is to be found nowhere else than in its modes and ways of being, living and existing – that pale blue flower thriving in that grassland with those insects and animals. Each mode is identical to life and each mode is a difference of life, and there is no separation to be found. But what is truly awful is the human war of identities – from the sexual to the cultural, national and religious – that fabulates separation and breeds hatred and an obsession to find an enemy.

A common belonging to the Earth and life is, without exclusion, all of us; yet there is an individual who considers itself an enterprise and being unto itself, and separable from everybody else. It is the individual of individualism. Do not underestimate the extent to which this individual holds centre place, yet the “political” of today is to know and acknowledge that absolutely no one can live, survive or speak from that place alone. It demands that we see that any place, at the centre or not, is always opening onto other places and that this makes a common participation. We are all in it together, even with all those diverse languages spoken on planet Earth.

Today there are so many cries arising from the damage inflicted and many that sound nothing like a human voice. That the cries being heard sound nothing like a human voice means that some of us – us that do have human voices – can hear other-than-human languages. Are we going to speak of this? In the 2022 interview, “How to Develop a Planetary Consciousness,” Achille Mbembe bids us all to do just that. But before we can do that, we must dispense with the belief that only humans speak, “that what distinguishes us is that we mastered language and others didn’t.” Speech, as with subjectivity, isn’t the monopoly of humans. Plants speak. Forests speak. Some of us have learned to listen to those languages; it is an ancient practice, and, today, no one listening can block out those cries.

My words are not a lecture, nor a sermon; rather a call, at once intimate and public: the planet is one and no nation-state owns it. It means humans can’t think themselves as separable from what is planetary. What’s more, try as you may to find it, there is no definitive human being, no “human” of all humans (there is no definitive woman, no “woman” of all women). Humans form a varied mixture. I could even say, humans form a motely. Humans are mixed up with so much that is non-human, and this affirms the affective life that happen across planet Earth and which makes every individual, be it a human, a forest, a butterfly or river, profoundly transindividual. For a new planetary consciousness, it is time – and just – to love ourselves as this. Yet what casts a dark shadow over the human motely (and all of life) is an insatiable appetite for energy, which has resulted in so much extraction – coal, oil, gas, water, minerals, plants, trees, animals – and the destruction of peoples and communities. So often unthinking and, at worse, brutal and cruel, and it is far from stopping.

My words are not a lecture, nor a sermon; rather a cry: it is just that planetary inseparability isn’t ignored. And it is equally just that the damage done to life and planet Earth isn’t ignored. Both justice and connaissance are called for. It means coming together and going beyond the confines of nation-states, the antagonisms of business, identity, and religion, and to generate knowledge together.

In another essay, “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” 1942, Simone Weil says, “justice is so beautiful a thing.”[7] Her words give me insight and inspiration. Humanity consists of mixed bodies, and it happens across the human and the nonhuman, and justice shows its beauty when this very distinction fades and enables a fundamental equality to be seen. What is not just is for anyone to believe, because of wealth, class, fame, political or intellectual clout, they are superior to others. To say, “I despise your poverty” smacks justice in the face. When food and shelter is given to those who have little or none this isn’t charity; it is justice. When those who have been driven out of their homes or habitats and attention and care are given this isn’t charity; it is justice. When those who have been persecuted by a diabolical regime of oppression and in fleeing are welcomed with open arms this isn’t charity; it is justice. Yes, justice is so beautiful a thing.

And then the oppression. Every day the oppression, the fucking oppression. How many times can you wipe away the tears as humans tear themselves apart, tear the world apart and stomp cruelly on it, on each other and so many other living things. And in the name of what – an identity, a nation, a religion, getting rich or just pure power? From blown up cities and human bodies to rainforests razed to the ground, images of destruction dominate visual culture today. And what also dominates is an obsession with visibility driven by social media. Being seen online has become a competition for attention. We want attention and, at the same time, our attention is captured. As Ash Sarkar says in Minority Rule: Adventures in the Culture Wars, 2025: “Eyeballs covert into ad revenue, and delicious data that can be harvested. This is the material attention economy: the system that sucks up our time and focus and sells it.”[8] It too is a form of oppression, even if we don’t acknowledge it.

Many have spoken up about oppression. I, too, am speaking up for a world without oppression and separation. And as I speak up, I listen to others speaking up. And what I hear are so many different languages, so many different voices, human and non-human. What I hear is a beautiful din. It is planetary and it is political speech like no other.

[1] Simone Weil, On the Abolition of All Political Parties, trans. Simon Leys (NY: New York Review Books, 2013).

[2] Weil, On the Abolition of All Political Parties, 4.

[3] Weil, On the Abolition of All Political Parties, 4.

[4] Weil, On the Abolition of All Political Parties, 34.

[5] Weil, On the Abolition of All Political Parties, 25.

[6] Achille Mbembe, “How to Develop a Planetary Consciousness” [interview with Nils Gilman and Jonathan S. Blake], Noema, 11 January 2022, https://www.noemamag.com/how-to-develop-a-planetary-consciousness/.

[7] Simone Weil, “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” Waiting for God (Routledge Classics, 2021), 92.

[8] Ash Sarkar, Minority Rule: Adventures in the Culture Wars (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2025), 61.

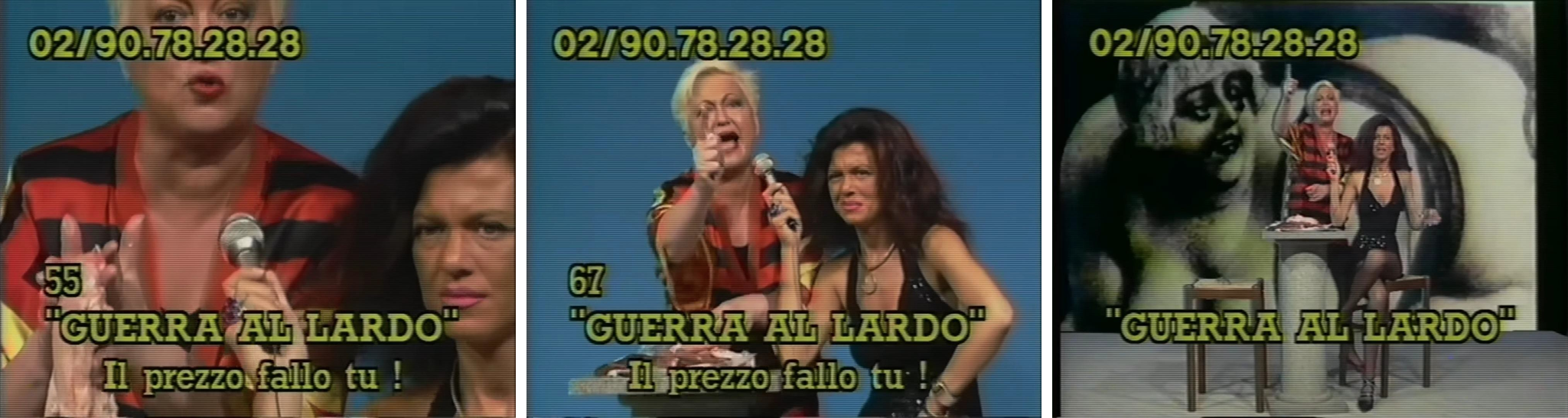

Mad About Justice (2022, Yve Lomax), courtesy of the artist.

Yve Lomax is a visual artist, writer, and editor (currently with Copy Press publishers, which she also directs, and its audio-visual platform Becoming Fireflies). Since the late 1970s, she has exhibited nationally and internationally. Her published work includes Writing the Image (2000), Pure Means (2014), Figure, Calling (2017), Nearness (2019), and Here from There (2024; co-authored with Vit Hopley). Previously she worked as Senior Research Tutor at the Royal College of Art and Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths, University of London. Besides feminism and the photographic image, a longstanding concern of hers has been writing for spoken performances, filmic examples of which include Political Life (2021) and Mad About Justice (2022).

Yve Lomax, “More than ever do we need to think,” JVC Magazine, 25 March 2025, https://journalofvisualculture.org/more-than-ever-do-we-need-to-think/