In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a new crew of transgressive graffiti artists landed on the hallowed and exclusive grounds of New York’s tony galleries. Primarily composed of African-American and Puerto-Rican youth, they transformed New York’s skyline, subway walls, and subway cars into their own personal canvases and composed new spaces of aesthetic expression amidst anti-graffiti laws, disapproving mayors, and a hostile New York City Transportation authority.[1] Soon, the works of these creative teens and young adults became so appreciated and respected by the lily-white art world that many of them ended up voyaging into a post-graffiti artistic career involving Neo-Expressionism and Afro-futurism. Among them was Jean-Michel Basquiat. Basquiat also played an important role in the growth and development of a hip-hop Black futurity in the visual arts, music, and fashion. Yes, this futurity was not always one painted with optimism, particularly when we observe his depiction of the rocket or spaceship and the Black male. While cultural critics like Greg Tate and Mark Dery have pointed out the futuristic import of Basquiat’s use of robot/alien hybrid creatures, the ongoing political significance of Basquiat’s use of the rocket or the spaceship has largely been unaddressed.[2]

I suggest that Basquiat’s rockets and spaceships offer continuous troublesome conveyance of the Black body’s movement in US-American society, as is most palpable in his 1984 work UFOs (Figure 1). In UFOs, Basquiat does not exhibit Afro-futurism in a celebratory way, but as a possible escape hatch. Art historian Laurie A. Rodrigues points to Basquiat’s desire to display escape from commodified American Africanism and perceived knowledge of Blackness before and during the twentieth century with his utilization of words, symbols, and figures.[3] But the fact that aspects of the work, with bold direct lines and simple shapes, appear to have been by a child belies a sophisticated leap into the everlasting.

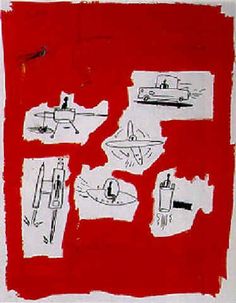

|

Figure 1. Jean-Michel Basquiat, UFOs, 1983, acrylic on paper, |

Basquiat has been the subject of scholarship in contemporary art history and theory for his complex depictions of Black heroes, celebrities, fellow artists, athletes, and musicians. Almost all of this scholarship has focused on of the ways he has interwoven (and reshaped in the process) graffiti’s forms and methods with African and Afro-Caribbean traditions, spirituality, and styles, the pictorial legacies of colonialism and slavery (e.g., as seen in his skeletal Black male bodies or skulls), and Neo-Expressionism.[4] Richard Marshall, in particular, has detailed the movements and styles at play in the years preceding and contemporaneous with Basquiat’s post-graffiti emergence. For Marshall, these movements and styles provided more aesthetic receptivity to Basquiat’s flat and linear black skeletal figurations and words of sociopolitical bent through the Imagist renderings of Phillip Guston and Susan Rothenberg, the Neo-Expressionist hands of Francesco Clemente, David Salle, and Jonathan Borofsky, and the political works of Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger.[5] Yet, unlike the more affirmative and sometimes confrontational Afro-futurist works by his contemporaries such as Rammellzee, Futura, Kool Kor, and Keith Haring, Basquiat’s image of technological advances in transportation clashes with the reality of Black alienation in the modern world.

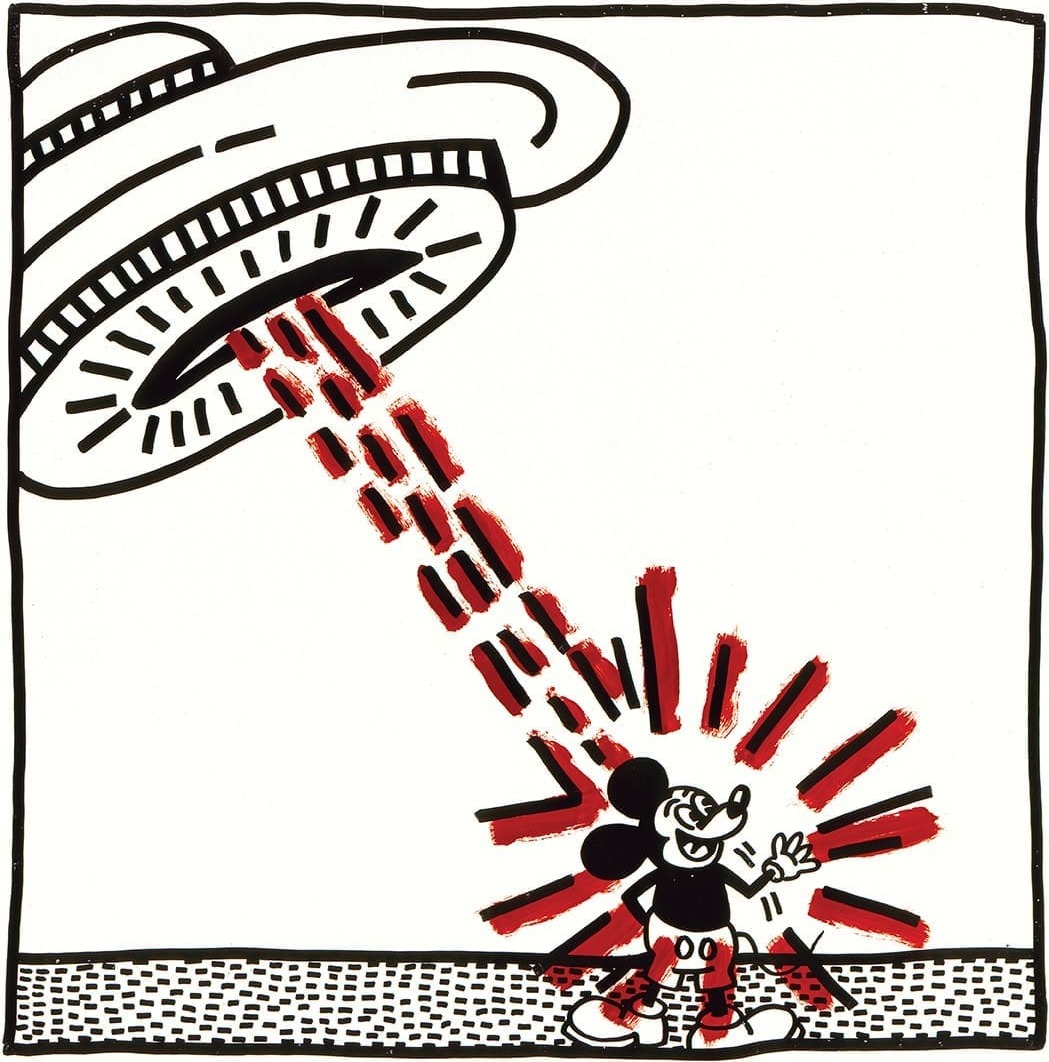

Figure 2. Keith Haring, Untitled, 1981, enamel on fiberboard, 48 x 48 in., courtesy of Rubell Museum, Miami.

For example, we see flights of fancy and fantasy in Haring’s Untitled (1981), which makes repetitive use of the UFO zapping the bodies of barking dogs, anthropomorphic creatures, adult humans, babies, pyramids and even Mickey Mouse as they dance and grin (Figure 2). Concentrated space beams safely penetrate earthly flesh and architecture causing us to believe that transportation is a benign experience for Haring’s characters. They can travel up and down, to other worlds and to Earth without fear from alien or earthly harm no matter the colour or contour of their bodies. Moreover, Haring’s zaps are benevolent, unlike the sometimes-fatal electrical circuitry of Tasers utilized by law enforcement on minorities including Miami graffiti artist Israel Hernandez-Llach in 2013. Contrarily, Basquiat’s UFOs exhibits ubiquitous earthly Black anxieties in the ordinary shape of a Black human pilot without transforming the Black body into a space alien or robot shape as is done in some of his other works such as Mississippi Alien/St. Louis Alien and Molasses (Figure 3) both dated 1983.

Figure 3. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Molasses, 1983, acrylic and oilstick on canvas, 60 x 84 in., private collection (licenced by Artestar, New York).

Greg Tate clearly states that Basquiat created boxers of alien robotic design that are analogous to the robots created by his post-graffiti contemporaries. “Some of these militant figures are mutant-robot hybrid creatures, which further underscores the alignment of JMB’s Afrofuturism with Futura’s robots, Fab 5 Freddy’s space gods, Haring’s aliens and animalisms, and Rammellzee’s pyrotechnic and combat-ready sound suits.”[6] Yet, a dystopian and more visibly relatable vision of uncertainty and death sits with the human shaped Black driver, pilot, or astronaut. For Basquiat, Black mechanical futurity is one where the plain Black figure travels simply to evade capture, not to create a brand-new world and speak a new alien language of freedom. In this work, he does not create a celebrity or athlete confronting societal ills head on. Basquiat’s figure is anonymous and wholly Black. It is the color of his skin that we notice in each vehicle. Basquiat offers no expression in any of the figures’ faces. We attempt to decipher the emotions of the figure, but they remain indecipherable. The lack of facial features and expressions give the figure a stock-like appearance. He is one of many Black figures traveling, but where to? Basquiat’s Black pilot or astronaut does not land safely, but instead falls from grace into perpetual gravitational fields of racial strife and disaster in scientific marvels.

Basquiat’s noted admiration for Leonardo da Vinci’s sense of invention and mastery of drawing informs his use of Jetsons-like spaceships and rockets alongside planes and automobiles.[7] Yet, his ingenuity and inclusion of the Black male within these vehicles raises a question absent in relevant scholarship: Can the Black male survive his travels within such vehicles and upon his exit from them—not only yesterday but also today and tomorrow? The question is not whether the Black figure possesses the acumen to invent or drive these vehicles, but the permission to reach safe shores.

Basquiat’s acrylic depiction of a Black man attempting to enter different spaces is doomed and mired in infinite solitary confinement. The irony of self-criticism and negative African-American characterizations embedded in American society is one painted by Basquiat and others. It allows us to view Basquiat’s Black pilot as a figure who is alone in this world and the next—as an unwelcome alien in all atmospheres.[8] He is a pilot on his way to the next galaxy with no clear route to relief. Neither cars and planes nor spaceships have sufficed to transport this man to spaces of universal peace and harmony—whether on Earth or elsewhere. In fact, his pilot’s expired spaceship registration or lack of fuel sometimes leads to a one-way flight.

In 2024, thirty-six years after his untimely death at the age of twenty-seven, Basquiat’s artworks now travel to a new generation with similar but better televised problems. This is a generation that has witnessed online a plethora of young Black men and women killed by white law enforcement officers, leading to protest movements such as Black Lives Matter. It has also seen the even more despondent occasions on which Black law enforcement officers seem to internalize centuries of racial hatred and brutally attack and kill Black citizens attempting to escape “traffic stops” (the technical term for being pulled over by the police). While violence against the Black body continues to be inflicted by various state actors otherwise positioned differently along the colour line, technology has equipped federal and state prosecutors with new visual and auditory opportunities to depict criminal acts. The body-worn video camera and the smartphone capture expected and unexpected violence. In fact, what is seized here involves not only images of anti-Black hatred but also the pitfalls of the assumption that technological advancements suffice to engender political progress.

All the body cameras in the world could not alert in real time other law enforcement entities or the public and block the physical assaults on the lean frame of Tyre Nichols in Memphis, Tennessee in 2023. Specifically, there were four body-cameras as well as streetlight-mounted pole cameras on the scene as an unarmed twenty-nine-year-old father, Tyre Nichols, was beaten to death by five Black police officers on January 7, 2023 during a traffic stop. Two officers pleaded guilty and testified against their fellow members of the so-called Scorpion crime unit, a special police force devoted to rooting out high levels of crime in Memphis, Tennessee. Tyre was pulled over for an alleged traffic violation, pepper sprayed and tasered. He never recovered from the beatings. A number of the officers have been convicted of federal witness tampering, obstruction of justice, and lesser civil rights violations resulting in bodily injury, with some also awaiting state murder trials. None of these developments, however, changes the fact that Tyre Nichols is no longer here on this planet with his young son. During his lifetime, Basquiat painted the death of a young Black graffiti artist, Michael Stewart, who had been beaten to death for an alleged graffiti violation and possibly resisting arrest.[9] Four decades on, running a red light or spray painting a subway wall still leads to the same death sentence for the young Black American male.

Nichols’ attempts to flee from the Black Memphis police officers and the chaos and death that ensued recall Basquiat’s UFOs. The Black male appears to be trapped—framed—in his automobile or spaceship. Basquiat’s lone Black figure can utilize the spaceship to escape his planet’s oppressive structures and inhumane treatment. But the numerous spaceships and futuristic vehicles portrayed in the painting have yet to even fully take off let alone enter outer space. They hover, float, eject into the atmosphere, but do not access a safe Black space. They are each surrounded by an amorphous white shape and then a blood-red background. implying an escape that is not a peaceful sojourn into Blackness but an entry into a bloodbath. The solitary Black figure is seated or standing in each vehicle — be it a helicopter, flying car, rocket ship, spaceship, or airplane in cramped confinement. Instead of liberatory mobility, the vehicle ends up serving incarceration. Its driver is not free even as he boards a vehicle that promises salvation through mobility.

The six transportation vehicles face various directions: north, south, east, west. These Black figures are departing not simply as individuals at different times. Instead, we are witnessing the escape of several Black pilots in simultaneity and close proximity. The implication is that they will all crash and burn into each other upon departure. Unity breeds strength, but not in the case of mass departure. What we frightfully encounter is a cataclysmic collision. Each vehicle departs from an anonymous landing spot with no air traffic controller or NASA station from which to launch. It is therefore unclear whether the pilots seek to travel to the other side of the world or another universe. Basquiat brings together a conglomerate of exodus vehicles for interplanetary travel and sits the Black male figure in the pilot’s seat with no clear destination or galactic itinerary. What’s more, the figure does not wear any astronaut gear to protect him from the harsh physical conditions of outer space and its lack of oxygen. Perhaps, Basquiat has seen the Black man’s trouble to breathe on planet Earth in the first place.

In his 1910 Futurist Manifesto, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti unequivocally states that Futurists have no need for critics and that there is no room for imitation or references to the past in Futurist works. “Why should we look back over our shoulders, when we intend to breed the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and space died yesterday.”[10] This is direct contrast with Basquiat’s allusions to the lingering legacies of colonialism, slavery, and anthropomorphic creatures. As seen in Italian Futurism’s inextricable relationship with Fascism, the idea that time and space could be left behind is not only a racialized privilege but also the basis of an aesthetics that sustains and reproduces violent social structures.[11] For those who are corporeally reminded time and again that time and space is violently alive for them, the only possible Futurism is one that disturbs any association it might have with a clean break with history and geography by working from spatial and temporal situatedness. Pain and suffering are conditions and structures of the global colonial Black past. In the case of Italian Futurism, the inability to leave space and time behind confronted the artists as the experience of disappointment with institutional politics at a specific historical juncture where their ideas had indeed been incorporated into institutional politics. But, in Basquiat, this inability is a collectively embodied Black experience that derives from a long history of racialized/racializing structures in the US. There is no disappointment as such here. Precisely because time and space are the subject of embodied experience that drives from longstanding (and ongoing) histories, leaving time and space behind is not simply a question of “visions” that are achieved or not and one where, if the vision is not realized by institutional politics, the artist becomes disappointed. Rather, leaving this particular time and this particular space of whiteness is (and has always been, for more than four centuries now) an urgent political imperative in its own right. Basquiat’s UFOs reminds us that evasion remains an eternal form of resistance for the Black figure. Its failure results not from institutional politics failing to meet the vision of artists but rather from the success of institutional politics in retaining its founding and systemic elements and extending their structuring role into the future.

On the other hand, the representation of danger and new machine technologies is one that Marinetti, Boccioni, and other Italian Futurists would have appreciated in the works of Basquiat and other post-graffiti artists. Yet, the stakes were not equivalent. European Italian futurists faced political volatility due to their support or disavowal of Fascist policies. Graffiti artists faced danger at the hands of local law enforcement, even when spraying walls and subways in their own blighted and abandoned neighbourhoods, left decrepit from white suburban flight and ineffective economic and social policies in urban neighbourhoods from the 1970s through 1980s.[12] City authorities did not appreciate the artistic flourishing of lower-class minority art on government and private walls. In 1980s New York, graffiti artists routinely encountered fines, arrest, detainment and physical violence at the hands of New York transportation authorities as they attempted to flee.

Time and space are very much alive in the legacies of racism and discrimination that manifest in traffic stops. Basquiat paints a dubious trail and destination for the Black astronaut and pilot. The weight of the otherwise invisible colonial baggage derails his optimistic flight towards the future. The same trip to nowhere continues to characterize a long list of fateful traffic stops inflicted upon Leonard Cure, Emmanuel Millard, Darcel Edwards, Jarveon Hudspeth, Demarcus Brodie, and others. Art historian William Ian Bourland has identified that several artists, politicians, and cultural critics have bemoaned white lunar exploration at the expense of disinvestment in poor, urban, Black communities.[13] Basquiat delineates the Black male figure as a subject for lunar or galactic travel but for the purposes of absolute survival, not curiosity.

From the Black slave seeking to escape by foot or on horseback from the deadly sugar plantations of the Caribbean and the American South, US-American Black families taking the train North to evade lynching during Jim Crow, to the minor traffic violator driving his Toyota Camry a little too quickly, we see Basquiat’s brushstrokes in UFOs as a crash course in the history of Black flight.

[1] Greg Tate, “Hip-Hop’s Afro-futuristic Hive Mind,” Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, eds. Liz Munsell and Greg Tate (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2020), 152.

[2] Mark Dery, “Black to the Future,” Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, ed. Mark Dery (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 182.

[3] Laurie A. Rodrigues, “SAMO© as an Escape Clause”: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Engagement with a Commodified American Africanism, Journal of American Studies 45, no. 2 (May 2011): 230, 234.

[4] We read about Basquiat’s transition from street artist to Neo-Expressionist in a variety of media including books, journal articles, newspaper articles, interviews, and video. An inexhaustive list includes Tate and Munsell, eds., Writing the Future; Jordana Moore Saggesse, Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Jordana Moore Saggesse, The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews and Critical Responses (Oakland: University of California, Press, 2021); Rene Ricard, Robert Farris Thompson, Greg Tate, Dick Hebdige and others compiled in Richard Marshall, ed., Basquiat (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art and Harry N. Abrams, 1992).

[5] Richard Marshall, “Repelling Ghosts,” Jean-Michel Basquiat, ed. Richard Marshall (New York: Abrams, 1992), 15.

[6] Tate, “Hip Hop’s Afro-futuristic Hive Mind,”154.

[7] Examples of Eurocentrically canonical references utilized by Basquiat include African Rock Art by Burchard Brentjes; the 1996 volume of Leonardo da Vinci, published by Reynal & Company, New York. Symbol Source-book: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols by Henry Dreyfuss; Gray’s Anatomy; and a few others. See Robert Farris Thompson, “Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets: The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” Jean-Michel Basquiat, ed. Richard Marshall (New York: Abrams, 1992), 23.

[8] Richard Schur, “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art,” African American Review 41, no. 4 (Winter 2007): 645.

[9] J. Faith Alimiron, “We are the Upsetters: The Social Consciousness of Basquiat and Rammellzzee,” Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, eds. Liz Munsell and Greg Tate (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2020), 128.

[10] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” Futurism: An Anthology, eds. Lawrence Rainey et al. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 49-53.

[11] Anne Bowler, “Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism,” Theory and Society 20, no. 6 (December 1991): 763-764.

[12] Carla McCormick, “In the Beginning was the Word: An Origin Story,” Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, ed. Liz Munzell and Greg Tate (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2020), 14.

[13] William Ian Bourland, “Afronaauts: Race in Space,” Third Text 34, no. 2 (2020): 220.

Danelle Bernten is a PhD student in art history. Her primary interests are African-American art, arts of the African diaspora, Southern art, and art criticism. She is the recipient of a 2024 National Committee for the History of Art Graduate Travel Fellowship to Lyon, France, and the FSU MLK, Jr. Book Award. Her writing has appeared in Number: Inc., InLiquid, Journal of Art Crime, and Ruckus Journal.

Cite as

Danelle Bernten. “Basquiat’s Black-Eyed Beams,” JVC Magazine, 2 May 2025, https://www.journalofvisualculture.org/basquiats-black-eyed-beams